[lang_fr]

– Meilleurs joueurs d’hier

– Champions du monde

[/lang_fr]

[lang_en]

– Top players from the past

– World champions

[/lang_en]

[lang_fr]

| Robert James Fischer | |

|

|

|

Bobby Fischer à Leipzig en 1960

|

|

|

|

|

| Surnom(s) | Bobby Fischer |

|---|---|

| Naissance | 9 mars 1943 Chicago, États-Unis |

| Décès | 17 janvier 2008 (à 64 ans) Reykjavík, Islande |

| Nationalité | |

| Profession(s) | Joueur d’échecs |

| Distinctions | Champion du monde d’échecs |

Robert James Fischer dit Bobby Fischer, né le 9 mars 1943 à Chicago et mort le 17 janvier 2008 à Reykjavík, est un joueur d’échecs américain naturalisé islandais en 2005. Champion des États-Unis à quatorze ans en 1957-1958, il est devenu Champion du monde en 1972 en remportant, sur fond de guerre froide, le « match du siècle » à Reykjavík, contre le Soviétique Boris Spassky.

Garry Kasparov a déclaré en 2008 que « Fischer peut tout simplement être considéré comme le fondateur des échecs professionnels et sa domination, bien que de très courte durée, a fait de lui le plus grand joueur d’échecs de tous les temps ». Fischer a contribué de façon décisive, par ses revendications lors des tournois, à l’amélioration des conditions financières et matérielles des joueurs d’échecs professionnels.

Après s’être retiré de toutes les compétitions en 1972, Fischer a disputé en 1992, à Belgrade, un match revanche contre son adversaire de 1972, Boris Spassky, en violation de l’embargo proclamé par le département d’État américain. Menacé de poursuites par son propre pays, Fischer a terminé sa vie en exil au Japon puis en Islande. Il y a multiplié les déclarations antisémites et anti-américaines.

Biographie et carrière

Famille et enfance (1943-1949)

Bobby Fischer est né à Chicago en 1943. Les parents de Bobby, Gerhardt Fischer, biophysicien allemand né à Berlin en 1909, et Regina Wender, divorcèrent en 1945 deux ans après la naissance de leur fils. Regina Wender (1913 – 1997), américaine d’ascendance juive allemande, était née hors des États-Unis, en Suisse, et avait été éduquée à Saint-Louis. À 19 ans, en 1932, elle avait rejoint son frère à Berlin pour étudier. La même année, elle y fit la connaissance de Gerhard. En 1933, ils quittèrent l’Allemagne nazie et partirent à Moscou, où ils se marièrent en 1938. En 1939, Régina retourna aux États-Unis avec leur fille née en 1938, mais sans son mari.

En 2002, une enquête menée par deux journalistes du Philadelphia Enquirer a montré qu’il était probable que le père biologique de Fischer fût en réalité le physicien juif hongrois Paul Nemenyi qui avait émigré aux États-Unis la même année que Regina Fischer, en 1939. Quand Nemenyi participait au projet Manhattan en tant qu’ingénieur à Washington, le FBI soupçonna Nemenyi d’être communiste et Regina d’être une espionne russe. En effet, Regina avait étudié à la faculté de médecine de Moscou, en 1933, où elle avait passé cinq ans avant d’émigrer aux États-Unis après son mariage. Le FBI tint un dossier sur Regina. Elle avait fait la connaissance de Nemenyi au Colorado en 1942, et après la naissance de Bobby, le physicien lui envoya chaque mois une somme d’argent. Les versement continuèrent jusqu’à la mort de Nemenyi, en 1952.

Bobby ne vit jamais Gerhard Fischer, puisque ses parents étaient séparés à sa naissance, selon le dossier que tenait le FBI. Pendant et après la guerre, Regina exerça plusieurs métiers, dont celui de soudeuse dans les chantiers navals de Portland. En 1948, Regina, qui avait trouvé un emploi d’institutrice, et ses deux enfants déménagèrent d’abord dans le sud de Los Angeles, puis à Phoenix et à Mobile dans l’Arizona, une ville isolée au milieu du désert. C’est la mère de Bobby Fischer qui s’occupait de son éducation et de celle de Joan, son aînée de six ans ainsi que de sept autres élèves venus des ranchs alentours. Les Fischer s’installèrent un an plus tard à Brooklyn où Régina voulait terminer ses études de médecine à l’université de New York et obtenir un diplôme d’infirmière.

Débuts aux échecs (1949-1955)

Un jour de 1949, Joan, pour distraire son petit frère, lui acheta un Monopoly, un jacquet, et un jeu d’échecs au bazar du coin. Les deux enfants apprirent seuls les règles à l’aide du feuillet joint au jeu. Ce n’était au début qu’un jeu comme les autres pour Bobby. Néanmoins, la lecture d’un livre contenant des parties d’échecs pendant les vacances changea la donne. Regina, sa mère, a raconté que lorsqu’il lisait ce livre, il était inutile d’essayer de lui adresser la parole.

En 1950, la mère de Bobby chercha des adversaires pour son fils, et Hermann Helms l’invita à affronter Max Pavey lors d’une séance de partie simultanée en janvier 1951. Bobby Fischer raconta plus tard que sa défaite le motiva beaucoup. Par la suite, Regina inscrivit Bobby au Brooklyn Chess Club où il vint tous les vendredis soir, multipliant les parties. Il participa à son premier championnat du Brooklyn Chess Club à l’âge de dix ans. Il termina cinquième en 1953, et troisième-cinquième ex æquo en 1954 ou 1955. En mai 1955, il finit trente-deuxième au championnat amateur des États-Unis, puis en juillet, lors du championnat junior des États-Unis 1955, il se classa dixième-vingtième ex æquo avec deux victoires, deux défaites et six parties nulles. À la différence de José Raúl Capablanca et Samuel Reshevsky, Fischer ne fut donc pas un enfant prodige. En revanche, ses progrès furent très rapides. À l’été 1955, Bobby, n’ayant plus de rivaux dignes de ce nom dans le club de Brooklyn, s’inscrivit alors au Manhattan Chess Club, fréquenté par les meilleurs joueurs du pays et qui organisa par la suite le championnat des États-Unis.

Champion des États-Unis à quatorze ans (1956 – 1958)

Bobby Fischer jouant contre son entraineur John William Collins, vers 1958.

En 1956, Bobby Fischer fait la connaissance de son entraineur John William (Jack) Collins. Il remporte, du 9 au 15 juillet 1956, le championnat junior des États-Unis à Philadelphie à sa deuxième tentative, ce qui constitue son premier réel succès. Puis, du 16 au 28 juillet, il s’essaye au championnat open adulte des États-Unis à Oklahoma City et se classe quatrième ex æquo avec trois autres joueurs, sans perdre une seule partie. Au mois d’octobre, il est invité au plus fort tournoi américain de l’année 1956 : le troisième trophée Rosenwald (Lessing Rosenwald était le sponsor de la fédération américaine). Il termine huitième (+2 -4 = 5) de ce tournoi remporté par Samuel Reshevsky. Sa victoire spectaculaire contre Donald Byrne lors la huitième ronde fit le tour du monde et attira l’attention des journalistes sur lui. Lors des vacances de Thanksgiving, en novembre 1956, il termina deuxième ex æquo du tournoi open des états de l’est (Eastern states open) à Washington sans concéder la moindre défaite.

L’année suivante, en mars 1957, Fischer affronta l’ancien champion du monde Max Euwe dans un match exhibition ; Fischer perdit 0,5 à 1,5 (une partie nulle et une défaite). En juillet, il conserva son titre de champion national junior en ne concédant qu’une partie nulle mais la fédération américaine décida d’envoyer William Lombardy au championnat du monde junior 1957 qui se tiendrait à Toronto. En août 1957, Fischer réussit à conquérir le championnat open des États-Unis à Cleveland sans perdre une partie, devançant grâce à un meilleur départage Arthur Bisguier ; puis il finit ses vacances scolaires en devenant le champion de l’état du New-Jersey (fin août-début septembre) en ne concédant qu’une seule partie nulle, marquant 6,5 points sur 7.

À la fin de l’année 1957, Fischer fut invité au quatrième trophée Rosenwald organisé du 17 décembre au 8 janvier. Ce tournoi était également le championnat des États-Unis 1957-1958, ainsi que le tournoi zonal qualificatif pour le tournoi interzonal, tournoi de sélection pour championnat du monde d’échecs. Il le remporte à quatorze ans sans perdre une partie, avec huit victoires et cinq nulles.

Grand maître à quinze ans (1958-1959)

Fischer (à droite) avec Bill Lombardy (à gauche) et leur entraîneur, Jack Collins.

En janvier 1958, Fischer est devenu champion des États-Unis (adultes) à l’âge de 14 ans. Grâce à ce titre, il est qualifié pour participer au tournoi interzonal qui constitue l’étape obligatoire vers le titre de champion du monde. Cependant, personne n’est prêt à parier sur la qualification du jeune Fischer (les six premiers du tournoi interzonal étant qualifiés pour le tournoi des candidats). C’est donc une surprise lorsqu’il termine cinquième ex æquo de cette compétition, ce qui lui permet de se voir conférer le titre de grand maître international. Ce record de précocité ne fut battu qu’en 1991, par Judit Polgár.

En décembre 1958–janvier 1959, Fischer remporta pour la deuxième fois le championnat des États-Unis. En mars 1959, dès qu’il eut seize ans, il quitta l’école secondaire. Plus tard, il déclarerait que le moment qu’il préférait à l’école était la sonnerie qui indiquait la fin des cours. Dans une interview donnée en août 1961, il dit : « On n’apprend rien à l’école. C’est juste une perte de temps. (…) Ils donnent trop de devoirs scolaires. On ne devrait pas avoir de devoirs à faire. Cela n’intéresse personne. Les professeurs sont stupides. Il ne devrait pas y avoir de femmes. Elles ne savent pas enseigner. Et on ne devrait obliger personne à aller à l’école. Si tu ne veux pas y aller, tu n’y vas pas, c’est tout. C’est ridicule. Je ne me souviens de rien que j’aie appris à l’école. (…) J’ai gaspillé deux années et demi à Erasmus High. Je n’ai rien aimé. Tu dois te mêler avec tous ces enfants stupides. Les professeurs sont même plus idiots que les enfants. Ils parlent de haut aux enfants. La moitié d’entre eux sont fous. S’il m’avaient laissé choisir, je serais parti avant d’avoir eu seize ans. » Cette interview fit beaucoup de tort à l’image de Fischer dans les médias lorsqu’elle parut, en janvier 1962.

En avril 1959, il partit en Argentine et au Chili pour disputer deux tournois. Lors du tournoi de Zurich de mai 1959, il battit pour la première fois un joueur soviétique, le grand maître Paul Keres, et finit 3e ex æquo avec Keres derrière Tal et Gligoric. En septembre et octobre, il prit comme secondant Bent Larsen lors du tournoi des candidats au championnat du monde de Bled, Zagreb et Belgrade, et termina premier joueur non soviétique à la cinquième place ex æquo avec Glogoric, derrière les quatre joueurs soviétiques Tal, Keres, Petrossian et Smyslov, mais devant Olafsson et Benko. Il marqua :

- 0 / 4 contre le futur champion du monde Tal ;

- 1 / 4 contre le futur champion du monde Petrossian (+0 –2 =2) ;

- 2 / 4 contre Kéres (+2 –2 =0), Smyslov (+1 –1 =2) et Gligoric (+1 –1 =2) ;

- 2,5 / 4 contre Olafsson (+2 –1 =1) ;

- 3 / 4 contre Benko (+2 –0 =2).

Succès internationaux (1960–1961)

Bobby Fischer à l’olympiade de Leipzig, en 1960.

En 1960, après son troisième titre de champion des États-Unis (1959-1960), Fischer remporta ses deux premiers tournois internationaux : Reykjavik, et, ex æquo avec Boris Spassky, le tournoi de Mar del Plata (au printemps).

À partir de 1960, les relations entre Bobby Fischer et sa mère se dégradèrent. À seize ans, il avait quitté l’école contre l’avis de sa mère qui pensait qu’il consacrait trop de temps aux échecs. Regina Fischer s’était inscrite au Comité pour l’action non violente (CNVA), un mouvement pour la paix. Elle participa à une marche pour la paix de huit mois, prévue en décembre 1960, qui devait aller de San Francisco à Moscou. Elle rencontra un professeur d’Anglais et partit s’installer avec lui en Angleterre. Elle ne réapparut dans la vie de son fils qu’en 1972, et mourut en 1997.

À l’automne 1960, Fischer remporta la médaille de bronze au premier échiquier avec l’équipe des État-Unis à l’ olympiade de Leipzig. En janvier 1961, il remporta son quatrième titre de champion des États-Unis, toujours sans perdre de partie. Pendant l’été (en juillet-août), il disputa un match contre l’ancien prodige américain Samuel Reshevsky. Le match fut interrompu sur un score d’égalité (+2 –2 =7) suite à un désaccord : la douzième partie avait été avancée à onze heure le dimanche matin pour satisfaire le mécène du match, Mme Piatigorsky. Opposé à cet aménagement, Fischer ne se présenta pas à la rencontre et fut déclaré perdant par forfait. Il refusa de disputer une treizième partie si la douzième n’était pas rejouée. Reshevsky fut déclaré vainqueur du match et Fischer poursuivit la fédération américaine devant le tribunal. L’affaire se termina par un non-lieu mais le scandale fut relayé dans les médias (presse, radio et télévision) et ternit l’image de Fischer.

En septembre 1961, Fischer marqua 3,5 points sur 4 contre les quatre joueurs soviétiques qui participaient au tournoi de Bled (Slovénie) : il battit pour la première fois Mikhaïl Tal, Tigran Petrossian et Efim Geller, et annula contre Paul Keres. Seul l’ancien champion du monde Tal le devança au tableau final. À la fin de l’année, Fischer ne participa pas au championnat de 1961-1962 mais resta en Europe pour se préparer au tournoi interzonal qui devait avoir lieu à Stockholm de janvier à mars 1962.

Échec à Curaçao (1962)

En mars 1962, Fischer remporta le tournoi interzonal de Stockholm avec 17,5 points sur 22 et deux points et demi d’avance sur les soviétiques Petrossian, Geller et Kortchnoï. Fischer était le premier joueur à devancer les Soviétiques dans un tournoi majeur d’échecs depuis 1946.

Fischer avait été, dès l’âge de 16 ans, candidat au titre mondial. Lors de sa deuxième tentative au tournoi des candidats de mai et juin 1962, il n’eut pas la réussite escomptée. À Curaçao, il finit quatrième avec seulement 14 points sur 27. Il marqua :

- 1,5 / 4 contre le futur champion du monde Petrossian (+0 –1 =3), contre Geller (+1 –2 =1) et Kortchnoï (+1 –2 =1) ;

- 2 / 4 contre Kéres (+1 –1 =2) ;

- 2,5 / 4 contre Benko (+2 –1 =1) ;

- 2 / 3 contre l’ancien champion du monde Tal (+1 –0 =2) qui avait abandonné lors du dernier tour du tournoi ;

- 3 / 4 contre Filip (+2 –0 =2).

Après le tournoi, il dénonça la collusion entre les trois premiers du tournoi, Tigran Petrossian, Paul Keres et Efim Geller, qui auraient conclu de courtes parties nulles entre eux pour préserver leur énergie contre lui. En 1965, la FIDE changea les règles du cycle de qualification en organisant des matches par élimination directe plutôt qu’un tournoi toutes rondes.

Retrait des compétitions internationales (1963-1965)

Après son échec au tournoi des candidats en 1962, Fischer accusa les soviétiques de complot pour conserver le titre de champion du monde et écarter les joueurs des autres nations. Il décida de boycotter les compétitions internationales organisées par la Fédération internationale — tournoi interzonal et olympiade d’échecs — en 1964. Le seul tournoi de haut niveau qu’il disputa entre février 1963 et août 1965 fut le championnat des États-Unis 1963-1964, qu’il remporta en marquant 100 % des points (ne concédant aucune partie nulle et aucune défaite, avec 11 points marqués sur 11). Il n’y eut pas de championnat des États-Unis en 1964-1965.

Retour avorté dans le circuit des tournois (1965-1968)

La FIDE répondit aux accusations de Fischer en remplaçant le tournoi des candidats par des matchs éliminatoires. En août–septembre 1965, Fischer effectua son retour dans les tournois internationaux, disputant le tournoi mémorial Capablanca de La Havane par télex depuis New York. En 1967, après avoir remporté le championnat des États-Unis pour la huitième fois, Fischer revint en Europe et termina premier des tournois de Skopje et de Monaco. Il se retira du tournoi de qualification de Sousse en Tunisie, qu’il dominait largement (sept victoires et trois parties nulles), parce qu’il refusait d’affronter consécutivement plusieurs joueurs soviétiques sans avoir de jour de repos, et parce qu’il demandait à ne pas disputer de parties le samedi, selon les préceptes de l’Église adventiste du septième jour. Brouillé par les conditions de son exclusion, il ne participa qu’à deux tournois en 1968 (Natanya en Israël et Vinkovci en Croatie). En 1968, Fischer quitta New York et déménagea à Los Angeles. En 1969, l’éditeur Simon et Schuster publia son recueil de parties My Sixty memorable Games, mais Fischer ne disputa aucune compétition.

La conquête du championnat du monde (1970-1972)

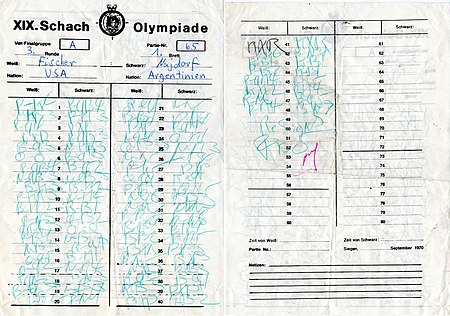

feuille de la partie Fischer-Najdorf, disputée à l’olympiade de Siegen en 1970.

En mars 1970, Fischer revint à la compétition pour disputer le match URSS– Reste du monde, qui avait lieu à Belgrade. Il accepta de jouer au deuxième échiquier et battit l’ancien champion du monde Tigran Petrossian : 3–1 (+2 –0 =2). Il enchaîna en remportant le tournoi blitz de Herceg Novi, puis les tournois de Rovinj–Zagreb (tournoi de la paix) et de Buenos-Aires, devançant à chaque fois largement tous ses adversaires. À la fin de l’année, Fischer, qui n’avait pas disputé le championnat des États-Unis qualificatif pour le championnat du monde, fut repêché grâce au désistement de dernière minute de son compatriote Pal Benko, pour disputer le tournoi de qualification interzonal de Palma de Majorque qui se tenait du 9 novembre au 12 décembre. Après un très bon départ, il subit une petite baisse de régime, mais se ressaisit sur la fin en remportant ses 7 dernières parties (dont l’ultime par forfait) pour gagner le tournoi avec 3,5 points d’avance sur ses plus proches poursuivants. Fischer renouvela sa performance du tournoi de Bled 1961 en marquant 3,5 points sur 4 contre les quatre participants soviétiques de l’interzonal : seul Polougaïevski parvint à annuler sa partie, tandis que Smyslov, Geller et Taïmanov perdirent contre Fischer.

Par la suite, lors des matchs éliminatoires pour le Championnat du monde, il écrase le Soviétique Mark Taimanov par le score de 6 à 0 au mois de mai 1971, à Vancouver au Canada, puis il écrase le Danois Bent Larsen sur le même score de 6 à 0, malgré la conviction du maître danois de sa victoire en juillet 1971, à Denver, aux États-Unis. Le match de qualification suivant l’oppose à Tigran Petrossian, joueur réputé pour sa solidité en défense, à Buenos Aires, au mois de septembre 1971. Après une défaite de chaque côté et trois parties nulles, Fischer aligne quatre gains et vainc l’ancien champion du monde par 6,5 à 2,5. Avant de perdre une partie contre Petrossian, Fischer avait établi une série de 20 victoires consécutives contre des GMI (sans aucune partie nulle) en parties officielles, un record à ce niveau.

À l’issue d’un match mémorable en Islande, surnommé le match du siècle, qui tint le public en haleine autant pour les parties que pour les péripéties hors compétition (menace de Fischer de ne pas participer, forfait lors de la deuxième partie, ses exigences sur le placement des caméras ou l’absence de contact avec le public, etc.), il devient champion du monde à l’été 1972, en battant finalement assez facilement le Russe Boris Spassky, champion du monde sortant. Ce succès, largement médiatisé, met temporairement fin à 24 ans d’hégémonie soviétique sur le monde des échecs, et est un tournant dans la compétition entre les États-Unis et l’URSS, en pleine guerre froide à l’époque.

Retraite (1973-1991)

Fischer ne disputa plus aucune partie officielle (tournoi ou match) après qu’il eut conquit ce titre mondial. En 1975, il perdit son titre par forfait pour avoir refusé les conditions du match dont le but était de remettre son titre en jeu contre son adversaire désigné, le jeune Soviétique Anatoli Karpov (contre qui il n’aura jamais disputé la moindre partie).

Depuis 1975 et l’abandon de son titre, sa personnalité a basculé dans une paranoïa grandissante, notamment contre les Juifs et les États-Unis qu’il accuse de comploter contre lui. Dans un de ses articles, Steve A. Furman a attribué le comportement de Bobby Fischer à un trouble psychiatrique, le syndrome d’Asperger, mais le joueur d’échecs et psychiatre islandais Magnus Skulason, qui connaissait le joueur, n’est pas d’accord avec ce diagnostic. Lors d’une audience du Comité permanent de la justice et des droits de la personne, le Dr Louis Morissette cita Fischer comme exemple de schizophrénie paranoïde.

En 1989, il avait déposé un brevet pour une pendule d’échecs qui ajoutait un certain temps supplémentaire pour chaque coup joué, afin d’éviter le « Zeitnot ». La « cadence Fischer » a été depuis adoptée par la Fédération internationale des échecs et est souvent pratiquée en tournoi dans la dernière phase de jeu. En 1996, il créa une variante du jeu d’échecs : les échecs aléatoires Fischer (Fischer Random Chess) ; il a refusé depuis de jouer une partie qui ne se déroulerait pas selon ces règles.

Match revanche contre Spassky (1992)

Bobby Fischer avait disparu complètement du monde échiquéen pour ne réapparaître qu’en 1992, pour un match revanche contre Boris Spassky, match que les organisateurs et Fischer ont qualifié abusivement de « championnat du monde », Fischer prétextant ne jamais avoir perdu son titre de 1972 sur l’échiquier. Ce championnat du monde non officiel se tint en Yougoslavie, alors en pleine guerre civile, et sous embargo des États-Unis. Fischer remporta à nouveau le duel, et empocha la somme de 3,35 millions de dollars. Il fut alors poursuivi dans son propre pays pour violation de l’embargo et fraude fiscale ; il risquait une peine concrète de dix ans d’emprisonnement.

Exil et clandestinité (1993-2003)

Poursuivi par les États-Unis depuis 1992, Fischer séjourna plus ou moins clandestinement dans divers pays, la Hongrie, les Philippines, l’Argentine et le Japon, aidé par ses sympathisants. Il y fit quelques brèves apparitions médiatiques, notamment pour des déclarations antisémites très controversées. Le 11 septembre 2001, quelques heures après les attentats de New York et de Washington, interrogé par Pablo Mercado, il s’emporte sur les ondes de Radio Bombo aux Philippines : « C’est une formidable nouvelle, il est temps que ces putains de juifs se fassent casser la tête. Il est temps d’en finir avec les États-Unis une bonne fois pour toutes. (…) Je dis : mort aux États-Unis ! Que les États-Unis aillent se faire foutre ! Que les juifs aillent se faire foutre ! Les juifs sont des criminels. (…) Ce sont les pires menteurs et salauds ! On récolte ce qu’on a semé. Ils ont enfin ce qu’ils méritent. C’est un jour merveilleux. »

Arrestation au Japon et asile politique en Islande (2004-2008)

Tombe de Bobby Fischer à Reykjavik.

Le 13 juillet 2004, alors qu’il tente de s’envoler pour Manille, il se fait arrêter à l’aéroport de Tokyo-Narita parce que son passeport américain a été annulé à son insu ; il est placé pendant neuf mois dans le centre de détention pour étrangers d’Ushiku au nord-est de Tokyo en attendant son extradition. En décembre 2004, devant l’émoi international causé par sa détention, il demande l’asile politique à l’Islande, lieu de la conquête de son titre de champion du monde. Il obtient finalement la citoyenneté islandaise le 22 février 2005, et il peut rejoindre ce pays le 24 mars. Le département d’État américain se déclare alors déçu.

En septembre 2004, il épouse Miyoko Watai, joueuse d’échecs amateur et présidente de la fédération japonaise avec qui il vivait depuis 2000 ; elle l’accompagne en Islande.

Il décède à 64 ans en Islande, le 17 janvier 2008, des suites d’une défaillance rénale. À sa mort, l’ancien champion du monde Garry Kasparov a déclaré que « Fischer peut tout simplement être considéré comme le fondateur des échecs professionnels et sa domination, bien que de très courte durée, a fait de lui le plus grand de tous les temps ».

Palmarès

Sources :

- Les parties d’échecs de Bobby Fischer de Wade et O’Connell (1972)

- Bobby Fischer de Frank Brady (1973).

1958 – 1962 : premières compétitions internationales

Après sa défaite contre Max Euwe, lors d’un match exhibition en 1957, les seules compétitions où Fischer termina avec un score négatif furent le tournoi des candidats de 1959 (12,5 points sur 28 et 0 à 4 contre Mikhaïl Tal) et le tournoi international de Buenos Aires 1960 où Fischer finit treizième-seizième ex æquo avec 8,5 points sur 19.

1963 – 1972 et 1992 : l’ascension vers le championnat du monde

Après 1962, Fischer termina premier ou deuxième de toutes les compétitions auxquelles il participa.

Championnats des États-Unis (1957 – 1967)

Lorsque Fischer débuta sa carrière, il n’y avait pas eu de championnat des États-Unis organisé depuis 1955. En 1956, il termina 4e-8e du championnat open des États Unis, puis 8e-9e (+2 =5 -4) du troisième trophée Rosenwald qui rassemblait les meilleurs joueurs américains mais ne comptait pas encore comme championnat des États-Unis. L’année suivante, Fischer remporta le championnat open des États-Unis 1957 et le quatrième trophée Lessing-Rosenwald (1957-1958) organisé à New York, qui compta comme championnat des États-Unis. En 1957, ainsi que lors des éditions suivantes, Fischer gagna le titre avec au moins un point d’avance sur le deuxième.

Fischer avait perdu contre le champion des États-Unis de 1954, Arthur Bisguier, lors de la première ronde du troisième trophée Rosenwald de 1956 ; par la suite, il annula leur partie lors du championnat open de 1957, puis il remporta les treize parties qu’ils disputèrent ensuite. Avant la dernière ronde du championnat de 1962-1963, Bisguier et Fischer étaient à égalité (avec 7 points sur 10), car lors de la première ronde, Fischer avait subi sa première défaite en championnat depuis 1957. Cependant, les deux joueurs ne s’étaient pas encore rencontrés. Lors de la dernière ronde, Bisguier gâcha une position prometteuse, perdant à la fois la partie et le titre de champion des États-Unis.

En 1963-1964, Fischer remporta toutes ses parties ; en 1965-1966, il en perdit deux ; puis, après la huitième victoire en 1966-1967, il considéra que le nombre de participants au championnat des États-Unis était insuffisant, et cessa de participer au championnat.

Olympiades d’échecs

Fischer face à Tal lors de l’olympiade de 1960.

Lors des olympiades, Fischer a gagné deux médailles d’argent (en 1966 et 1970) et une médaille de bronze (en 1960) individuelles, et deux médailles d’argent par équipe (en 1960 et 1966).

Ses affrontements contre le premier échiquier de l’équipe d’URSS représentaient à chaque fois l’attraction des olympiades.

- En 1960, il affrontait le nouveau champion du monde Mikhaïl Tal ; la partie fut une nulle très disputée.

- En 1962, Fischer affrontait Mikhaïl Botvinnik. Il gagna un pion lors de l’ouverture (une défense Grünfeld), mais laissa échapper le gain lors de l’ajournement. Cette partie est la seule que Fischer joua jamais contre Botvinnik. Les analyses de Fischer occupent 14 pages dans son ouvrage Mes soixante meilleures parties. Une armée d’analystes soviétiques s’est escrimée à prouver que Botvinnik tenait la nulle dans toutes les variantes d’une position très complexe (finale Tours et pions).

- En 1966, le champion du monde Tigran Petrossian se défila et laissa jouer Boris Spassky à sa place. La partie fut nulle.

- En 1970, Fischer rencontra le champion du monde Boris Spassky et utilisa une nouvelle fois la défense Grunfeld avec les Noirs ; il perdit la partie.

| Année | Lieu | Classement et médaille individuels |

Score | Classement de l’équipe des États-Unis |

Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Leipzig | Troisième | Bronze | 13 / 18 | +10 -2 =6 | Deuxième | Médaille d’or remportée par Robatsch devant Tal. |

| 1962 | Varna | Huitième | 11 / 17 | +8 -3 =6 | Quatrième | Reshevsky était absent. Fischer ne marqua que 5,5 sur 11 en finale. |

|

| En 1964, Fischer boycotta l’olympiade de Tel-Aviv. | |||||||

| 1966 | La Havane | Deuxième | Argent | 15 / 17 | +14 -1 =2 | Deuxième | Médaille d’or remportée par Petrossian |

| En 1968, Fischer boycotta l’olympiade de Lugano. | |||||||

| 1970 | Siegen | Deuxième | Argent | 10 / 13 | +8 -1 =4 | Quatrième | Fischer perdit contre Spassky. Médaille d’or remportée par Spassky. |

Fischer aura aussi affronté une fois les champions soviétiques Youri Averbakh, Mikhaïl Botvinnik, Lev Polougaïevski (parties terminées par la nulle) et Vladimir Toukmakov (une victoire) ; et deux fois David Bronstein (deux nulles), Ratmir Kholmov (une victoire et une défaite) et Leonid Stein (une victoire et une nulle).

Mikhaïl Tal et Efim Geller furent les adversaires les plus difficiles à battre, pour Bobby Fischer. Avant le match de 1972, Spassky avait un score de trois victoires, deux parties nulles et aucune défaite contre lui.

Style échiquéen

Bobby Fischer reste célèbre pour son sens aigu d’analyse des variantes, comme l’atteste le texte (quasiment dépourvu de toute appréciation verbale) de son livre Mes soixante meilleures parties. Anthony Saidy a écrit qu’« une partie de Fischer est une construction logique où les moments tactiques découlent naturellement d’une stratégie exacte ». Saidy a ajouté que Fischer « traitait rationnellement le milieu de jeu, un peu dans le style de Capablanca jeune, et ses attaques étincelantes étaient celles d’un Alekhine ».

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position avant 19. Tf6!! (Fischer – Pal Benko, New York, 1963) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Le diagramme ci-contre (à gauche) montre un exemple de coup de tonnerre dans un ciel serein dont Fischer fit l’offrande au monde des échecs : dans sa partie contre Pal Benko du Championnat des Etats-Unis de 1963, à New York, Fischer joua : 19. Tf6!! pour bloquer le pion f7 des Noirs (si 19…Fxf6, le mat est inévitable après 20. e5). La partie se poursuivit par : 19…Rg8 20. e5 h6 21. Ce2 1-0.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fischer-Taïmanov, Vancouver, 1971 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Fischer – Mark Taïmanov, match des Candidats au Championnat du Monde, Vancouver, 1971, 2e partie

Dans cette position (diagramme de droite) très simplifiée, Fischer continua à jouer pour le gain, et l’obtint. Taïmanov, qui semblait croire la partie nulle déjà acquise, joua 81…Re4?, ce à quoi Ficher répliqua par 82. Fc8! (si 82…Cf3, alors 83. Fb7+ et si 82…Cd3, alors 83…Ff5+, et les Noirs ne peuvent plus empêcher que le pion blanc parvienne en h5).

Il suivit : 82…Rf4 83. h4 Cf3 84. h5 Cg5 85. Ff5 Cf3 86. h6 Cg5 87. Rg6 Cf3 88. h7 Ce5+ 89. Rf6 1-0. Fischer était toujours prêt à jouer des heures et des heures en plus pour arriver au gain plutôt qu’à la partie nulle.

Ouvertures favorites de Fischer et exemples de parties

Ouvertures avec les Noirs

Avec les Noirs, contre d4, les parties ci-dessous montrent la prédilection de Fischer pour la défense est-indienne et la défense Grünfeld, soit deux ouvertures tendues où les Noirs jouent pour la contre-attaque. Ces deux lignes de jeu impliquent un important travail préparatoire, ce en quoi Fischer fut un pionnier: il jouait peu d’ouvertures, mais il les connaissait à fond. Il en va de même pour sa défense de prédilection face à 1. e4: la variante du pion empoisonné de la Sicilienne Najdorf. Cette ligne de jeu entraîne une lutte à couteaux tirés, où la moindre inexactitude peut être synonyme de défaite.

Défense est-indienne

- Viktor Kortchnoï – Fischer, tournoi blitz de Herceg Novi, 1970, défense est-indienne

Kortchnoï, qui était un spécialiste de la défense est-indienne avec les Blancs, fut le seul joueur à remporter une partie contre Fischer dans le tournoi de Herceg Novi, joué immédiatement après le match URSS–Reste du monde, et qui fut considéré comme un championnat du monde Blitz malgré l’absence de Spassky.

1. d4 Cf6 2. c4 g6 3. Cc3 Fg7 4. e4 d6 5. Fe2 0-0 6. Cf3 e5 7. O-O Cc6 8. d5 Ce7 9. Cd2 c5 10. a3 Ce8 11. b4 b6 12. Tb1 f5 (les Noirs sont prêts pour lancer l’attaque côté roi.) 13. f3 f4 14. a4 g5 15. a5 Tf6 ! 16. bxc5 ? bxc5 17. Cb3 Tg6 18. Fd2 Cf6 (ou …h5!) 19. Rh1 g4 (ou 19…h5) 20. fxg4 (forcé à cause de la menace 20…g3 et si 21. h3 Fxh3 etc.) Cxg4 21. Tf3 ? (21. Ff3!) Th6 22. h3 Cg6 23. Rg1 Cf6 24. Fe1 Ch8 !! 25. Td3 Cf7 26. Ff3 Cg5 27. De2 Tg6 28. Rf1 (si 28 Rh2 Dd7 menace 29…Cxh3 etc.) Cxh3 29. gxh3 Fxh3+ 30. Rf2 Cg4+ 31. Fxg4 Fxg4 32. abandon. Il n’y a rien à faire contre la menace double 31…Fxe2 et 32…Dh4+.

- René Letelier – Fischer, Olympiade d’échecs de 1960, Leipzig, défense est-indienne

1. d4 Cf6 2. c4 g6 3. Cc3 Fg7 4. e4 0-0!? 5. e5?! Ce8 6. f4 d6 7. Fe3 c5! 8. dxc5 Cc6 9. cxd6? exd6 10. Ce4?! Ff5! 11. Cg3?! Fe6 12. Cf3 Dc7 13. Db1 dxe5 14. f5 e4! 15. fxe6 exf3 16. gxf3 f5! 17. f4 Cf6 18. Fe2 Tfe8 19. Rf2 Txe6 20. Te1 Tae8 21. Ff3? Txe3! 22. Txe3 Txe3 23. Rxe3 Df4+! 24. abandon (24. Rxf4 est impossible car le Roi Blanc est mat après Fh6, et Fischer avait analysé la suite : 24. Rf2 Cg4+ 25. Rg2 Ce3+ 26. Rf2 Cd4 27. Dh1 Cg4+ 28. Rf1 Cf3 qui gagne). Cette partie est révélatrice de la personnalité de Fischer: il jouait toujours pour le gain, quitte à venir « chercher l’adversaire sur son propre terrain » ; Fischer avait d’ailleurs en horreur les nulles de salon.

Défense Grünfeld

- Donald Byrne – Fischer, trophée Rosenwald 1956, défense Grünfeld

Défense Najdorf, variante du pion empoisonné

- Georgi Tringov – Fischer, La Havane, 1965, Sicilienne Najdorf, Variante du pion empoisonné

1. e4 c5 2. Cf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Cxd4 Cf6 5. Cc3 a6 6. Fg5 e6 7. f4 Db6 8. Dd2 Dxb2 9. Tb1 Da3 10. e5 dxe5 11. fxe5 Cfd7 12. Fc4 Fb4 13. Tb3 Da5 14. 0-0 0-0 15. Cxe6 fxe6 16. Fxe6+ Rh8 17. Txf8+ Fxf8 18. Df4 Cc6!! 19. Df7 Dc5+ 20. Rh1 Cf6!! 21. Fxc8 Cxe5! 22. De6 Ceg4! 0-1.

Ouvertures avec les Blancs

Avec les Blancs, à l’exception du Championnat du monde d’échecs de 1972, Fischer ouvrit presque toujours par 1. e4, qu’il jugeait « supérieur à tout autre coup, comme la pratique le démontre ». Il était un maître de la partie espagnole, aussi bien sous sa forme classique, qu’avec l’échange du Fou b5 contre le Cavalier c6. Contre la défense sicilienne, Fischer avait une prédilection pour le développement de son Fou f1 en c4, ce en quoi il n’a pas véritablement eu d’héritier au plus haut niveau. Il a été encore moins suivi dans son usage de l’attaque est-indienne. En résumé, si sur le plan des ouvertures Bobby Fischer peut dans une certaine mesure être comparé à Garry Kasparov à son époque (qui jouait lui aussi la défense est-indienne et la défense Grünfeld), ce dernier a laissé un héritage plus conséquent pour le monde des échecs, d’autant plus que Fischer s’est retiré très tôt des compétitions internationales. Le monde des échecs attendait monts et merveilles de Fischer après son titre de Champion du monde, et il fut un peu frustré par sa retraite anticipée.

[/lang_fr]

[lang_en]

Bobby Fischer

| Bobby Fischer | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Full name | Robert James Fischer |

| Country | United States Iceland |

| Born | March 9, 1943 Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Died | January 17, 2008 (aged 64) Reykjavík, Iceland |

| Title | Grandmaster |

| World Champion | 1972–1975 |

| Peak rating | 2785 (July 1972) |

Robert James « Bobby » Fischer (March 9, 1943 – January 17, 2008) was an American chess player and the eleventh World Chess Champion. He is widely considered one of the greatest chess players of all time. Fischer was also a best-selling chess author. After ending his competitive career, he proposed a new variant of chess and a modified chess timing system. Both ideas have received some support in recent years.

Widely considered a « chess legend », [1] [2] at age 13 Fischer won a “ brilliancy” that became known as The Game of the Century. Starting at age 14, he played in eight United States Championships, winning each by at least a point. At 15½, he became both the youngest Grandmaster and the youngest Candidate for the World Championship up until that time. He won the 1963–64 U.S. Championship 11–0, the only perfect score in the history of the tournament. In the early 1970s he became the most dominant player in modern history – winning the 1970 Interzonal by a record 3½-point margin and winning 20 consecutive games, including two unprecedented 6–0 sweeps in the Candidates Matches. According to research by Jeff Sonas, in 1971 Fischer had separated himself from the rest of the world by a larger margin of playing skill than any player since the 1870s. [3] He became the first official World Chess Federation ( Fédération Internationale des Échecs) ( FIDE) number one rated chess player in July 1971, and his 54 total months at number one is the third longest of all time.

In 1972, he captured the World Championship from Boris Spassky of the USSR in a match held in Reykjavík, Iceland that was widely publicized as a Cold War confrontation. The match attracted more worldwide interest than any chess match before or since. In 1975, Fischer declined to defend his title when he could not come to agreement with FIDE over the conditions for the match. He became more reclusive and did not play competitive chess again until 1992, when he won an unofficial rematch against Spassky. This competition was held in Yugoslavia, which was then under a United Nations embargo. [4] [5] [6] This led to a conflict with the U.S. government, and Fischer never returned to his native country.

In his later years, Fischer lived in Hungary, Germany, the Philippines, Japan, and Iceland. During this time he made increasingly anti-American and antisemitic statements, despite his Jewish ancestry. After his U.S. passport was revoked over the Yugoslavia sanctions issue, he was detained by Japanese authorities for nine months in 2004 and 2005 under threat of deportation. In February 2005, Iceland granted him right of residence as a « stateless » alien and issued him a passport. [7] When Japan refused to release him to Iceland on that basis, Iceland’s parliament voted in March 2005 to give him full citizenship. [8] The Japanese authorities then released him to that country, where he lived until his death in 2008. [9]

Early years

[Top page]

Bobby Fischer was born at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois on March 9, 1943. [10] His birth certificate listed his father as Hans-Gerhardt Fischer, a German biophysicist. His mother, Regina Wender Fischer, was an American citizen of Polish Jewish descent, [11] born in Switzerland and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. [10] She later became a teacher, a registered nurse, and a physician. [12] The couple married in 1933 in Moscow, USSR, where Regina was studying medicine at the First Moscow Medical Institute. They divorced in 1945 when Bobby was two years old, and he grew up with his mother and older sister, Joan. In 1948, the family moved to Mobile, Arizona, where Regina taught in an elementary school. The following year they moved to Brooklyn, New York, where she worked as an elementary school teacher and nurse.

A 2002 article by Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson of The Philadelphia Inquirer argued that Paul Nemenyi, a Hungarian Jewish physicist, was Fischer’s biological father. [13] [14] [15] The article quoted an FBI report which stated that Regina Fischer returned to the United States in 1939, while Hans-Gerhardt Fischer never entered the United States, having been refused admission by U.S. immigration officials because of alleged Communist sympathies. [13] [16] [17] Regina and Nemenyi were reported to have had an affair in 1942, and he made monthly child support payments to her, paying for Fischer’s schooling until his own death in 1952. [18] Fischer later told the Hungarian chess player Zita Rajcsanyi that Nemenyi would sometimes show up at the family’s Brooklyn apartment and take him on outings. [15] However, Regina Fischer told a social worker that she had traveled to Mexico to see Hans-Gerhardt in June 1942, and that Bobby was conceived during that meeting. [19]

In May 1949, the six-year-old Fischer and his sister learned how to play chess using the instructions from a chess set bought at a candy store below their Brooklyn apartment. [20] [21] When the family vacationed at Patchogue, Long Island that summer, Bobby found a book of old chess games, and studied it intensely. [22] On November 14, 1950, his mother sent a postcard to the Brooklyn Eagle, seeking to place an ad inquiring whether other children of Bobby’s age might be interested in playing him. The paper rejected her ad because no one could figure out how to classify it, but forwarded her inquiry to Hermann Helms, the « Dean of American Chess », who told her that master Max Pavey would be giving a simultaneous exhibition on January 17, 1951. [23] [24] Fischer played in the exhibition, losing in 15 minutes. One of the spectators was Carmine Nigro, president of the Brooklyn Chess Club, who introduced him to the club and began teaching him. [25] [26] Fischer attended the club regularly, intensified his interest, and gained playing strength rapidly. In the summer of 1955, the then 12-year-old Fischer joined the Manhattan Chess Club, the strongest in the country. [27] [28]

Regina Fischer protesting on Bobby’s behalf in front of the White House during the Eisenhower Administration [29]

In June 1956, Fischer began attending the « Hawthorne Chess Club », which was actually master John W. Collins’ home. Collins had earlier coached some of the country’s leading players, including Robert Byrne, Donald Byrne, and William Lombardy. Fischer played thousands of blitz and offhand games with Collins and other strong players, began studying the books in Collins’ large chess library, and ate almost as many dinners at Collins’ home as his own. [30] [31] [32] Future grandmaster Arnold Denker was also a mentor to young Bobby, often taking him to watch the New York Rangers play hockey at Madison Square Garden. Denker wrote that Bobby enjoyed those treats and never forgot them; the two became lifelong friends. [33]

Fischer was also involved with the Log Cabin Chess Club of Orange, New Jersey, which in March 1956 took him on a tour to Cuba, where he gave a 12-board simultaneous exhibition at Havana’s Capablanca Chess Club, winning 10 and drawing 2. [34] [35] On this tour the club played a series of matches against other clubs. Fischer played on second board, behind strong master Norman Whitaker. Whitaker and Fischer were the leading scorers for the club, each scoring 5.5 points out of 7 games. [36]

Fischer attended Erasmus Hall High School at the same time as Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond. [37] [38] In 1959, its student council awarded him a gold medal for his chess achievements. [39] [40] The same year, Fischer dropped out of high school when he turned age 16, the earliest he could legally do so. [41] [42] He later explained to Ralph Ginzburg, « You don’t learn anything in school. It’s just a waste of time. » [43]

When Fischer was 16, his mother moved out of their apartment to pursue medical training. Her friend Joan Rodker, who had met Regina when the two were « idealistic communists » living in Moscow in the 1930s, believes that Fischer resented his mother for being mostly absent as a mother, a communist activist and an admirer of the Soviet Union, and that this led to his hatred for the Soviet Union. In letters to Rodker, Fischer’s mother states her desire to pursue her own « obsession » of training in medicine and writes that her son would have to live in their Brooklyn apartment without her: « It sounds terrible to leave a 16-year-old to his own devices, but he is probably happier that way. » [44] The apartment was on the edge of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, which had one of the highest homicide and general crime rates in New York City. [45] Despite the alienation from her son, Regina in 1960 staged a five-hour protest in front of the White House (see photo) urging President Dwight Eisenhower to send an American team to that year’s chess Olympiad (set for Leipzig, East Germany, behind the Iron Curtain), and to help support the team financially. [29]

Young champion

[Top page]

Fischer experienced a « meteoric rise » in his playing strength during 1956. [46] On the tenth national rating list of the United States Chess Federation (USCF), published on May 20, 1956, his rating was a modest 1726, [47] over 900 points below top-rated Samuel Reshevsky (2663). [48] Fischer’s first real success was winning the United States Junior Chess Championship in July 1956. He scored 8½/10 at Philadelphia to become the youngest-ever junior champion at age 13, [49] a record that still stands. In the 1956 U.S. Open Chess Championship at Oklahoma City, Fischer scored 8½/12 to tie for 4th–8th places, with Arthur Bisguier winning. [50] In the first Canadian Open Chess Championship at Montreal 1956, he scored 7/10 to tie for 8–12th places, with Larry Evans winning. [51]

Fischer accepted an invitation to play in the Third Lessing J. Rosenwald Trophy Tournament at New York 1956, a premier tournament limited to the 12 players considered the best in the country. [52] Fischer received entry by special consideration, since his rating was certainly not among the top 12 in the country at that stage. In that elite company, the 13-year-old Fischer could only score 4½/11, tying for 8th–9th place. [53] This was his first truly strong round-robin event, and he achieved a creditable result, certainly above what his rating predicted. However, he won the first brilliancy prize for his game against Donald Byrne. [52] Hans Kmoch christened it » The Game of the Century », writing, « The following game, a stunning masterpiece of combination play performed by a boy of 13 against a formidable opponent, matches the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies. » [54] This game remains famous worldwide today. [55]

In 1957, Fischer played a two-game match against former World Champion Max Euwe at New York, losing ½–1½. [56] [57] On the United States Chess Federation’s eleventh national rating list, published on May 5, 1957, Fischer was rated 2231, a master – over 500 points higher than his rating a year before. [58] This made him at that time the country’s youngest master ever. [59] In July, Fischer successfully defended his U.S. Junior title, scoring 8½/9 at San Francisco. [60] In August, he played in the U.S. Open Chess Championship at Cleveland, scoring 10/12 and winning on tie-breaking points over Arthur Bisguier, [61] [62] making Fischer the youngest U.S. Open Champion ever. [63] He next won the New Jersey Open Championship, scoring 6½/7. [64] Fischer then defeated the young Filipino Master Rodolfo Tan Cardoso 6–2 in a match in New York sponsored by Pepsi-Cola. [65] [66]

Wins first U.S. title

[Top page]

Based on Fischer’s rating, the USCF invited him to play in the 1957–58 U.S. Championship. [67] This invitation required no special consideration, and was achieved on merit. The tournament included such luminaries as six-time champion Samuel Reshevsky, defending champion Bisguier, and William Lombardy, who in August had won the World Junior Championship with the only perfect score (11–0) in its history. [68] [69] Fischer was expected to score around 50%. Bisguier predicted that Fischer would « finish slightly over the center mark ». [68] [70] He scored eight wins and five draws to win the tournament with 10½/13, a point ahead of Reshevsky. [71] Still two months shy of his 15th birthday, he became the youngest U.S. champion in history [72] –- a record that still stands. [73] Since the championship that year was also the U.S. Zonal Championship, Fischer’s victory earned him the International Master title. [74] [75]

U.S. Championships

[Top page]

Fischer played in eight United States Chess Championships, each held in New York City, winning every one. [76] [77] His margin of victory was always at least one point. [78]

His scores were:

- 1957–58: 10½/13

- 1958–59: 8½/11

- 1959–60: 9/11

- 1960–61: 9/11

- 1962–63: 8/11

- 1963–64: 11/11

- 1965–66: 8½/11

- 1966–67: 9½/11. [76] [79]

Fischer missed the 1961–62 Championship (he was preparing for the upcoming Interzonal), and there was no 1964–65 event. [80] His total score was 74/90 (61 wins, 26 draws, 3 losses), with the only losses being to Edmar Mednis, Samuel Reshevsky, and Robert Byrne. [81] For his career, he achieved 82.2 percent in the U.S. Championship.

His 11–0 win in the 1963–64 Championship is the only perfect score in the history of the tournament, [82] [83] and one of about ten perfect scores in high-level chess tournaments ever. [84] [85] [86] David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld called it « the most remarkable achievement of this kind. » [84]

Olympiads

Fischer at the age of 17 playing world champion Mikhail Tal in Leipzig.

Fischer refused to play in the 1958 Munich Olympiad when his demand that he, as the reigning U.S. Champion, play first board ahead of Samuel Reshevsky was turned down. [87] According to some sources, Fischer, then 15, was unable to arrange leave from attending high school in order to play in Munich. [88] However, he represented the United States on top board with great distinction at four Olympiads:

-

Olympiad Individual result U.S. team result Leipzig 1960 13/18 (Bronze) Silver Varna 1962 11/17 (Eighth) Fourth Havana 1966 15/17 (Silver) Silver Siegen 1970 10/13 (Silver) Fourth

Fischer’s overall total was +40, =18, -7, for 49/65 or 75.4%. [89] [90] In 1966, he narrowly missed the individual gold medal, scoring 88.23% to World Champion Tigran Petrosian’s 88.46%. Fischer played four more games than Petrosian, faced stiffer opposition, and would have won the gold if he had accepted Florin Gheorghiu’s draw offer in the penultimate round rather than declining it and suffering his only loss. [91]

Fischer had planned to play for the United States at the 1968 Lugano Olympiad, but backed out when he saw the poor playing conditions. [92] [93]

Grandmaster, candidate, author

[Top page]

Fischer’s victory in the U.S. Championship qualified him to participate in the 1958 Portorož Interzonal, the next step toward challenging the World Champion. [66] The top six finishers in the Interzonal would qualify for the Candidates Tournament. [94] Prior to the Interzonal, he played two short training matches in Yugoslavia. He drew both games against Dragoljub Janoševic. Then he defeated Milan Matulovic in Belgrade by 2½–1½. [95]

Most observers doubted that a 15-year-old with no international experience could finish among the six qualifiers at the Interzonal, but Fischer told journalist Miro Radoicic, « I can draw with the grandmasters, and there are half-a-dozen patzers in the tournament I reckon to beat. » [96] Despite some bumps in the road, and a problematic start, Fischer succeeded in his plan: after a strong finish, he ended up with 12/20 (+6=12–2) to tie for 5th–6th. [97] The Soviet grandmaster Yuri Averbakh observed, « In the struggle at the board this youth, almost still a child, showed himself to be a fully-fledged fighter, demonstrating amazing composure, precise calculation and devilish resourcefulness. » [98] Fischer became the youngest person ever to qualify for the Candidates. He also became the youngest Grandmaster in history at 15 years and 6 months. This record stood until 1991 when it was broken by Judit Polgár. [99]

Before the Candidates’ tournament, Fischer competed in the 1958–59 U.S. Championship (winning with 8½/11) and then in international tournaments at Mar del Plata, Santiago, and Zürich. He played unevenly in the two South American tournaments. At the strong Mar del Plata event, he finished tied for third with Borislav Ivkov, half a point behind tournament winners Ludek Pachman and Miguel Najdorf; this confirmed his grandmastership. At Santiago, he tied for fourth through sixth places, behind Ivkov, Pachman, and Herman Pilnik. He did better at the very strong Zurich event, finishing a point behind world-champion-to-be Mikhail Tal and half a point behind Svetozar Gligoric. [100] [101]

Although Fischer had ended his formal education at age 16, he subsequently taught himself several foreign languages, to gain access to foreign chess periodicals. [102]

Until late 1959, Fischer « had dressed atrociously for a champion, appearing at the most august and distinguished national and international events in sweaters and corduroys ». [103] A director of the Manhattan Chess Club had once banned Fischer for not being « properly accoutered », forcing Denker to intercede to get him reinstated. [104] Likely, lack of money to buy better clothes was at least partially to blame. Now, encouraged by Pal Benko to dress more sharply, Fischer « began buying suits from all over the world, hand-tailored and made to order ». [105] [106] He boasted to journalist Ralph Ginzburg in 1961 that he had 17 suits, all hand-tailored, and that his shirts and shoes were also handmade. [107]

At the age of 16, Fischer finished a creditable equal fifth out of eight, the top non-Soviet player, at the Candidates Tournament held in Bled/ Zagreb/ Belgrade, Yugoslavia in 1959. He scored 12½/28 but was outclassed by tournament winner Tal, who won all four of their individual games. [108]

Fischer published his first book of collected games at age 16, in 1959. Entitled Bobby Fischer’s Games of Chess, and published by Simon & Schuster, the book sold well and made him likely the youngest author in the history of chess to that stage.

1960–61

[Top page]

In 1960, Fischer tied for first place with the young Soviet star Boris Spassky at the strong Mar del Plata tournament in Argentina, with the two well ahead of the rest of the field, scoring 13½/15. [109] Fischer lost only to Spassky, and this was the start of their relationship, which began on a friendly basis and stayed that way, in spite of Fischer’s troubles against him over-the-board. [110]

Fischer struggled in the later Buenos Aires tournament, finishing with 8½/19 (won by Viktor Korchnoi and Samuel Reshevsky on 13/19). [111] This was the only real failure of Fischer’s competitive career. [112] According to Larry Evans, Fischer’s first sexual experience was with a girl to whom Evans introduced him during the tournament. [113] [114] Pal Benko says that Fischer did horribly in the tournament « because he got caught up in women and sex. … Afterwards, Fischer said he’d never mix women and chess together, and kept the promise. » [115] Fischer concluded 1960 by winning a small tournament in Reykjavik with 4½/5, [116] and defeating Klaus Darga in an exhibition game in West Berlin. [117]

Reshevsky, Fischer, and José Ferrer

In 1961, Fischer started a 16-game match with Reshevsky, split between New York and Los Angeles. Despite Fischer’s meteoric rise, the veteran Reshevsky, 32 years Fischer’s senior, was considered the favorite, since he had far more match experience and had never lost a set match. [118] After 11 games and a tie score (two wins apiece with seven draws), the match ended prematurely due to a scheduling dispute between Fischer and match organizer and sponsor Jacqueline Piatigorsky. [119] Reshevsky was declared the winner of the match, and received the winner’s share. [120]

Fischer was second behind former World Champion Tal at Bled 1961, which had a super-class field. He defeated Tal head-to-head for the first time, scored 3½/4 against the Soviet contingent, and finished as the only unbeaten player, with 13½/19. [121]

1962: success, setback, collusion accusations

Dominates Interzonal

[Top page]

In the next World Championship cycle, Fischer won the 1962 Stockholm Interzonal by 2½ points, scoring an undefeated 17½/22. [122] He was the first non-Soviet player to win an Interzonal since FIDE instituted the tournament in 1948. [123]

Problems at Candidates’

[Top page]

Fischer’s decisive Interzonal victory made him one of the favorites for the Candidates Tournament in Curaçao, which began soon afterwards. [124] [125] He finished fourth out of eight with 14/27, the best result by a non-Soviet player, but well behind Tigran Petrosian (17½/27), Efim Geller, and Paul Keres (both 17/27). [126] Tal fell very ill during the tournament, and had to withdraw before completion. Fischer, a friend of Tal, was the only contestant who visited him in the hospital. [127]

Accuses Soviets of collusion

[Top page]

Following his failure in the 1962 Candidates (at which five of the eight players were from the Soviet Union), Fischer asserted in an August 1962 article in Sports Illustrated magazine, entitled The Russians Have Fixed World Chess, that three of the Soviet players ( Tigran Petrosian, Paul Keres, and Efim Geller) had a pre-arranged agreement to quickly draw their games against each other in order to save energy and to concentrate on playing against Fischer, and that a fourth, Viktor Korchnoi, had been forced to deliberately lose games to ensure that a Soviet player won the tournament. It is generally thought that the former accusation is correct, but not the latter. [128] [129] (This is discussed further in the World Chess Championship 1963 article.) Anatoly Karpov, later World Champion, wrote in his 1991 autobiography that Korchnoi had complained in the Soviet Union, shortly after the 1962 Candidates’ event, about not being included in the colluding group of Soviets. [130] Fischer also stated that he would never again participate in a Candidates’ tournament, since the format, combined with the alleged collusion, made it impossible for a non-Soviet player to win.

Following Fischer’s article, FIDE in late 1962 voted a radical reform of the playoff system, replacing the Candidates’ tournament with a format of one-on-one knockout matches; this was the format that Fischer would dominate in 1971. [131] [132]

Fischer defeated Bent Larsen in a summer 1962 exhibition game in Copenhagen for Danish TV. He also defeated Bogdan Sliwa in a team match against Poland at Warsaw later that year. [133]

In the 1962–63 U.S. Championship, Fischer had a close call. In the first round he lost to Edmar Mednis, his first loss ever in a U.S. Championship. Bisguier was in excellent form, and Fischer caught up to him only at the end. Tied at 7–3, the two met in the last round for the championship. Bisguier stood well in the middlegame, but blundered, handing Fischer his fifth consecutive U.S. championship. [134]

Religious transitions

[Top page]

In an interview in the January 1962 issue of Harper’s, Fischer was quoted as saying, « I read a book lately by Nietzsche and he says religion is just to dull the senses of the people. I agree. » [135] [136]

Fischer’s biological parents were likely both Jewish. Fischer renounced his Jewish roots, but joined the Worldwide Church of God in the mid-1960s. This church prescribed Saturday Sabbath, and forbade work (and competitive chess) on Sabbath. Fischer’s religious obligations were respected by chess organizers, concerning scheduling of his games. Fischer contributed significant money over several years to the Worldwide Church of God.

The year 1972 was a disastrous one for the Worldwide Church of God, as prophecies by Herbert W. Armstrong were unfulfilled, and the church was rocked by revelations of a series of sex scandals involving Garner Ted Armstrong. [137] Fischer, who felt betrayed and swindled by the Worldwide Church of God, left the church and publicly denounced it. [138]

Semi-retirement in the mid-1960s

[Top page]

Fischer declined an invitation to play in the 1963 Piatigorsky Cup tournament in Los Angeles, which had a world-class field. His decision was probably influenced by ill will over the aborted 1961 match against Reshevsky, which had been arranged by the same organizer. [139] Instead, he played in the Western Open in Bay City, Michigan, which he won with 7½/8. [140] In August–September 1963, he won another minor event, the New York State Championship at Poughkeepsie, with 7/7, his first perfect score. [141] [142]

The 1963–64 U.S. Championship was expected to be exciting, particularly since Fischer had only narrowly won it the previous year. It was, but not as expected. « One by one Fischer mowed down the opposition as he cut an 11–0 swathe through the field, to demonstrate convincingly to the opposition that he was now in a class by himself. » [139] This stunning result brought Fischer heightened fame, including a profile in Life magazine. [143] Sports Illustrated diagrammed each of the 11 games in its article, « The Amazing Victory Streak of Bobby Fischer ». [144] Such extensive chess coverage was groundbreaking for the top American sports magazine.

Fischer, eligible as U.S. champion, decided not to participate in the Amsterdam Interzonal in 1964, thus taking himself out of the 1966 World Championship cycle. [145] He held to this decision even when FIDE changed the format of the eight-player Candidates Tournament from a round-robin to a series of knockout matches, which eliminated the possibility of collusion. [143] He instead embarked on a tour of the United States and Canada from February through May, playing a simultaneous exhibition and giving a lecture in each of more than 40 cities. [146] His 94% winning percentage over more than 2,000 games is one of the best ever achieved. [147] Fischer also declined an invitation to play for the United States in the 1964 Olympiad in Tel Aviv. [148]

Successful return

[Top page]

Fischer wanted to play in the Capablanca Memorial Tournament, Havana 1965, but the State Department refused to endorse his passport as valid for visiting Cuba. [149] Fischer instead proposed, and the tournament officials and players accepted, a unique arrangement: Fischer played his moves from a room at the Marshall Chess Club, which were then transmitted by teletype to Cuba. [150] [151] [152] Ludek Pachman observed that Fischer « was handicapped by the longer playing session resulting from the time wasted in transmitting the moves, and that is one reason why he lost to three of his chief rivals ». [153] The tournament was an « ordeal » for Fischer, who had to endure eight-hour and sometimes even twelve-hour playing sessions. [154] Despite this handicap, he tied for second through fourth places, with 15/21, behind former World Champion Vasily Smyslov, whom he defeated in their individual game. [153] The tournament received extensive media coverage. [155] [156]

Fischer began 1966 by winning the U.S. Championship for the seventh time despite losing to Robert Byrne and Reshevsky in the eighth and ninth rounds. [157] [158] He also reconciled with Mrs. Piatigorsky, accepting an invitation to the very strong second Piatigorsky Cup tournament in Santa Monica. Fischer began disastrously and after eight rounds was tied for last with 3/8. He then staged « the most sensational comeback in the history of grandmaster chess », scoring 7/8 in the next eight rounds. At the end, World Championship finalist Boris Spassky edged him out by a half point, scoring 11½/18 to Fischer’s 11. [159] Now aged 23, Fischer would win every match or tournament he completed for the rest of his life. [160]

In 1967, Fischer won the U.S. Championship for the eighth and final time, ceding only three draws. [161] [162] In March–April and August–September, he won strong tournaments at Monte Carlo (7/9) and Skopje (13½/17). [163] [164] In the Philippines he played a series of nine exhibition games against master opponents, winning eight and drawing one. [165]

Withdraws while leading Interzonal

[Top page]

In the next World Championship cycle, at the 1967 Sousse Interzonal, Fischer scored a phenomenal 8½ points in the first 10 games, to lead the field. His observance of the Worldwide Church of God’s seventh-day Sabbath was honored by the organizers, but deprived Fischer of several rest days, which led to a scheduling dispute. Fischer forfeited two games in protest and later withdrew, eliminating himself from the 1969 World Championship cycle. Because he had completed less than half his scheduled games, all of his results were annulled, meaning players who had played him had those games cancelled. [131]

In 1968, Fischer won tournaments at Netanya (11½/13) and Vinkovci (11/13) by large margins. [166] He stopped playing for the next 18 months, except for a win against Anthony Saidy in a 1969 New York Metropolitan League team match. [167] [168]

In 1969, Fischer published his second games collection, entitled My 60 Memorable Games, which was also published by Simon & Schuster. He was assisted by his friend, GM Larry Evans. The book of deeply annotated games immediately became a best-seller, and has remained continuously popular worldwide to the present day.

World Champion

[Top page]

In 1970, Fischer began a new effort to become World Champion. His dramatic march toward the title made him a household name and made chess front-page news for a time. Chess statistician Jeff Sonas observes that « for about a year, Bobby Fischer dominated his contemporaries to an extent never seen before or since ». [169] He won the title in 1972, but forfeited it three years later.

Road to the world championship

Bobby Fischer’s scoresheet from his round 3 game against Miguel Najdorf in the 1970 Chess Olympiad in Siegen, Germany. Throughout his career, Fischer used the older descriptive chess notation system when recording his games, never switching to the modern algebraic system.

The 1969 U.S. Championship was also a zonal qualifier, with the top three finishers advancing to the Interzonal. Fischer, however, had sat out the U.S. Championship because of disagreements about the tournament’s format and prize fund. Benko, one of the three qualifiers, agreed to give up his spot in the Interzonal in order to give Fischer another shot at the world championship. [170] [171] [172]

Before the Interzonal, in March and April 1970, the world’s best players competed in the USSR vs. Rest of the World match in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, often referred to as « the Match of the Century ». Fischer allowed Bent Larsen of Denmark to play first board for the Rest of the World team in light of Larsen’s recent outstanding tournament results, even though Fischer had the higher Elo rating. [167] [173] The USSR team eked out a 20½–19½ victory, but on second board Fischer beat Tigran Petrosian, whom Boris Spassky had dethroned as world champion the previous year, 3–1, winning the first two games and drawing the last two. [174]

After the USSR versus the Rest of the World Match, the unofficial World Championship of Lightning Chess (5-minute games) was held at Herceg Novi. Petrosian and Tal were considered the favorites, [175] but Fischer overwhelmed the super-class field with 19/22 (+17=4–1), far ahead of Tal (14½), Korchnoi (14), Petrosian (13½), Bronstein (13), etc. [175] [176] Fischer lost only one game, to Korchnoi, who was also the only player to achieve an even score against him in the double round robin tournament. [177] [178] Fischer « crushed such blitz kings as Tal, Petrosian and Smyslov by a clean score ». [179] Tal marveled that, « During the entire tournament he didn’t leave a single pawn en prise! », while the other players « blundered knights and bishops galore ». [179] [180]

In April–May 1970, Fischer won easily at Rovinj/ Zagreb with 13/17 (+10=6–1), finishing two points ahead of a field that included such leading players as Gligoric, Hort, Korchnoi, Smyslov, and Petrosian. [181] [182] In July–August, he crushed the mostly grandmaster field at Buenos Aires, scoring 15/17 (+13=4) and winning by 3½ points. [183] In Siegen right after the Olympiad, he defeated Ulf Andersson in an exhibition game for the Swedish newspaper Expressen. [184] Fischer had taken his game to a new level. [185]

The Interzonal was held in Palma de Mallorca in November and December 1970. Fischer won it with a remarkable 18½–4½ score (+15=7–1), far ahead of Larsen, Efim Geller, and Robert Hübner, who tied for second at 15–8. [186] Fischer’s 3½-point margin set a new record for an Interzonal, beating Alexander Kotov’s 3-point margin at Saltsjöbaden 1952. [187] Fischer finished the tournament with seven consecutive wins (including a final-round walkover against Oscar Panno). [188] Setting aside the Sousse Interzonal (which Fischer withdrew from while leading), Fischer’s victory gave him a string of eight consecutive first prizes in tournaments. [170]

Fischer continued his domination in the 1971 Candidates matches. First, he beat Mark Taimanov of the USSR at Vancouver by 6–0. [189] « The record books showed that the only comparable achievement to the 6–0 score against Taimanov was Wilhelm Steinitz’s 7–0 win against Joseph Henry Blackburne in 1876 in an era of more primitive defensive technique. » [190]

Less than two months later, he astounded the chess world by beating Larsen in their Denver match by the same score. [191] [192] [193] Just a year before, Larsen had played first board for the Rest of the World team ahead of Fischer, and had handed Fischer his only loss at the Interzonal. Garry Kasparov later wrote that no world champion had ever shown a superiority over his rivals comparable to Fischer’s « incredible » 12–0 score in the two matches. [194] Chess statistician Sonas concludes that this victory gave Fischer the « highest single-match performance rating ever ». [195]

In August 1971, Fischer won a strong lightning event at the Manhattan Chess Club with a « preposterous » score of 21½/22. [176]

Only former World Champion Petrosian, Fischer’s final opponent in the Candidates matches, was able to offer resistance in their match, played at Buenos Aires. Petrosian played a strong theoretical novelty in the first game, gaining the advantage, but Fischer played resourcefully and eventually won the game after Petrosian faltered. [196] [197] [198] This gave Fischer an extraordinary run of 20 consecutive wins against the world’s top players (in the Interzonal and Candidates matches), a winning streak topped only by Steinitz’s 25 straight wins in 1873–82. [199] Petrosian won decisively in the second game, finally snapping Fischer’s streak. [200] After three consecutive draws, Fischer swept the next four games to win the match 6½–2½ (+5=3–1). [201] The final match victory allowed Fischer to challenge World Champion Boris Spassky, whom he had never beaten (+0=2–3). [202] Fischer appeared on the cover of Life. [203]

Fischer’s amazing results gave him a far higher rating than any player in history up until that time. [204] On the July 1972 FIDE rating list, his Elo rating of 2785 was 125 points ahead of Spassky, the second-highest rated player (2660). [205] [206]

World Championship Match

Fischer (at right) playing Spassky in 1972

Fischer’s career-long stubbornness about match and tournament conditions was again seen in the run-up to his match with Spassky. Of the possible sites, Fischer’s first choice was Belgrade, Yugoslavia, while Spassky’s was Reykjavik, Iceland. [207] For a time it appeared that the dispute would be resolved by splitting the match between the two locations, but that arrangement fell through. [208] After that issue was resolved, Fischer refused to appear in Iceland until the prize fund was increased. London financier Jim Slater donated an additional US$125,000 to the prize fund, bringing it to an unprecedented $250,000 ($1,267,825.63 in 2009 [209]), and Fischer finally agreed to play. [210]

Before and during the match, Fischer paid special attention to his physical training and fitness, which was a relatively novel approach for top chess players at that time. He had developed his tennis skills to a good level, and played frequently during off-days in Reykjavik. He also had arranged for exclusive use of his hotel’s swimming pool during specified hours, and swam for extended periods, usually late at night. [211]

The match took place in Reykjavík from July through September 1972. [212] Fischer lost the first two games in strange fashion: the first when he played a risky pawn-grab in a drawn endgame, the second by forfeit when he refused to play the game in a dispute over playing conditions. [213] Fischer would likely have forfeited the entire match, but Spassky, not wanting to win by default, yielded to Fischer’s demands to move the next game to a back room, away from the cameras whose presence had upset Fischer. [214] [215] After that game, the match was moved back to the stage and proceeded without further serious incident. Fischer won seven of the next 19 games, losing only one and drawing eleven, to win the match 12½–8½ and become the 11th World Chess Champion. [212]

The Cold War trappings made the match a media sensation. [216] It was called « The Match of the Century », [217] [218] [219] and received front-page media coverage in the United States and around the world. [220] [221] Fischer’s win was an American victory in a field that Soviet players had dominated for the past quarter-century — players closely identified with, and subsidized by, the Soviet state. [222] [223] Dutch grandmaster Jan Timman calls Fischer’s victory « the story of a lonely hero who overcomes an entire empire ». [224] [225]

Fischer became an instant celebrity. Upon his return to New York, a Bobby Fischer Day was held, and he was cheered by thousands of fans, a unique display in American chess. [226] He was offered numerous product endorsement offers worth « at least $5 million » (all of which he declined) [227] and appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated. [228] With American Olympic swimming champion Mark Spitz, he also appeared on a Bob Hope TV special. [229] Membership in the United States Chess Federation doubled in 1972 [230] and peaked in 1974; in American chess, these years are commonly referred to as the « Fischer Boom. » Fischer also won the ‘ Chess Oscar’ award for 1970, 1971, and 1972. This award, started in 1967, is determined through votes from chess media and leading players.

Forfeiture of title

[Top page]

Fischer was scheduled to defend his title in 1975. Anatoly Karpov eventually emerged as his challenger, having defeated Spassky in an earlier Candidates match. [231] Fischer, who had played no competitive games since his World Championship match with Spassky, laid out a proposal for the match in September 1973, in consultation with a FIDE official, Fred Cramer. He made three principal demands:

- The match should continue until one player wins 10 games, without counting the draws.

- There is no limit to the total number of games played.

- In case of a 9–9 score, champion (Fischer) retains his title and the prize fund is split equally. [232]

A FIDE Congress was held in 1974 during the Nice Olympiad. The delegates voted in favor of Fischer’s 10-win proposal, but rejected his other two proposals, and limited the number of games in the match to 36. [233] In response to FIDE’s ruling, Fischer sent a cable to Euwe on June 27, 1974:

- As I made clear in my telegram to the FIDE delegates, the match conditions I proposed were non-negotiable. Mr. Cramer informs me that the rules of the winner being the first player to win ten games, draws not counting, unlimited number of games and if nine wins to nine match is drawn with champion regaining title and prize fund split equally were rejected by the FIDE delegates. By so doing FIDE has decided against my participating in the 1975 world chess championship. I therefore resign my FIDE world chess champion title. Sincerely, Bobby Fischer. [234] [235]

The delegates responded by reaffirming their prior decisions, but did not accept Fischer’s resignation and requested that he reconsider. [236] Many observers considered Fischer’s requested 9–9 clause unfair because it would require the challenger to win by at least two games (10–8). [237] [238]

In a letter to Larry Evans, published in Chess Life in November 1974, Fischer claimed the usual system (24 games with the first player to get 12½ points winning, or the champion retaining his title in the event of a 12–12 tie) encouraged the player in the lead to draw games, which he regarded as bad for chess. Not counting draws would be « an accurate test of who is the world’s best player. » [239] Former U.S. Champion Arnold Denker, who was in contact with Fischer during the negotiations with FIDE, claimed that Fischer wanted a long match to be able to play himself into shape after a three-year layoff. [240]

Due to the continued efforts of U.S. Chess Association officials, [241] a special FIDE Congress was held in March 1975 in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands in which it was accepted that the match should be of unlimited duration, but the 9–9 clause was once again rejected, by a narrow margin of 35 votes to 32. [242] FIDE set a deadline of April 1, 1975, for Fischer and Karpov to confirm their participation in the match. No reply was received from Fischer by April 3 and Karpov officially became World Champion by default. [243] In his 1991 autobiography, Karpov expressed profound regret that the match did not take place, and claimed that the lost opportunity to challenge Fischer held back his own chess development. Karpov met with Fischer several times after 1975, in friendly but ultimately unsuccessful attempts to arrange a match. [244]

Sudden obscurity

[Top page]

After the World Championship in 1972, Fischer virtually retired from chess: he did not play a competitive game in public for nearly 20 years. [245] In 1977, he played three games in Cambridge against the MIT Greenblatt computer program, winning all of them. [246]

On May 26, 1981, a police patrolman arrested Fischer while he was walking in Pasadena, saying that he matched the description of a man who had just committed a bank robbery in that area. [247] Fischer stated that he was slightly injured during the arrest. [248] He was then held for two days and — according to Fischer — was subjected to assault and various other types of serious mistreatment during that time. [249] He was then released on $1000 bail. [250] After being released, Fischer published a 14-page pamphlet detailing his alleged experiences and saying that his arrest had been « a frame up and set up. » [251] [252] [253] [254]

In the early 1980s, Fischer stayed for extended periods in the San Francisco-area home of a friend, the Canadian Grandmaster Peter Biyiasas. In 1981, the two played 17 five-minute games. Despite his layoff from competitive play, Fischer won all of them, according to Biyiasas, who lamented that he was never even able to reach an endgame. [253] [254]

1992 Spassky rematch

[Top page]