L’Intelligence artificielle

[lang_fr]

L’intelligence artificielle, ou informatique cognitive, est la « recherche de moyens susceptibles de doter les systèmes informatiques de capacités intellectuelles comparables à celles des êtres humains ».

Le terme intelligence artificielle, créé par John McCarthy, est souvent abrégé par le sigle IA. Il est défini par l’un de ses créateurs, Marvin Lee Minsky, comme « la construction de programmes informatiques qui s’adonnent à des tâches qui sont, pour l’instant, accomplies de façon plus satisfaisante par des êtres humains car elles demandent des processus mentaux de haut niveau tels que : l’apprentissage perceptuel, l’organisation de la mémoire et le raisonnement critique ». On y trouve donc le côté « artificiel » atteint par l’usage des ordinateurs ou de processus électroniques élaborés et le côté « intelligence » associé à son but d’imiter le comportement. Cette imitation peut se faire dans le raisonnement, par exemple dans les jeux ou la pratique de mathématiques, dans la compréhension des langues naturelles, dans la perception : visuelle (interprétation des images et des scènes), auditive (compréhension du langage parlé) ou par d’autres capteurs, dans la commande d’un robot dans un milieu inconnu ou hostile.

Même si elles respectent globalement la définition de Minsky, il existe un certain nombre de définitions différentes de l’IA qui varient sur deux points fondamentaux :

- Les définitions qui lient la définition de l’IA à un aspect humain de l’intelligence, et celles qui la lient à un modèle idéal d’intelligence, non forcément humaine, nommée rationalité.

- Les définitions qui insistent sur le fait que l’IA a pour but d’avoir toutes les apparences de l’intelligence (humaine ou rationnelle), et celles qui insistent sur le fait que le fonctionnement interne du système IA doit ressembler également à celui de l’être humain ou être rationnel.

Deep Blue, le premier ordinateur à battre un champion du monde d’ échecs en titre.

Histoire

L’origine de l’intelligence artificielle se trouve probablement dans l’article d’ Alan Turing « Computing Machinery and Intelligence » (Mind, octobre 1950), où Turing explore le problème et propose une expérience maintenant connue sous le nom de test de Turing dans une tentative de définition d’un standard permettant de qualifier une machine de « consciente ». Il développe cette idée dans plusieurs forums, dans la conférence « L’intelligence de la machine, une idée hérétique », dans la conférence qu’il donne à la BBC 3e programme le 15 mai 1951 « Les calculateurs numériques peuvent-ils penser ? » ou la discussion avec M.H.A. Newman, AMT, Sir Geoffrey Jefferson et R.B. Braithwaite le 14 et 23 Jan. 1952 sur le thème « Les ordinateurs peuvent-ils penser? ».

On considère que l’intelligence artificielle, en tant que domaine de recherche, a été créée à la conférence qui s’est tenue sur le campus de Dartmouth College pendant l’été 1956 à laquelle assistaient ceux qui vont marquer la discipline. Ensuite l’intelligence se développe surtout aux États-Unis à l’ université Stanford sous l’impulsion de John McCarthy, au MIT sous celle de Marvin Minsky, à l’ université Carnegie Mellon sous celle de Allen Newell et Herbert Simon et à l’ université d’Édimbourg sous celle de Donald Michie. En France, l’un des pionniers est Jacques Pitrat.

Intelligence artificielle forte

Définition

Le concept d’intelligence artificielle forte fait référence à une machine capable non seulement de produire un comportement intelligent, mais d’éprouver une impression d’une réelle conscience de soi, de « vrais sentiments » (quoi qu’on puisse mettre derrière ces mots), et « une compréhension de ses propres raisonnements ».

L’intelligence artificielle forte a servi de moteur à la discipline, mais a également suscité de nombreux débats. En se fondant sur le constat que la conscience a un support biologique et donc matériel, la plupart des scientifiques ne voient pas d’obstacle de principe à créer un jour une intelligence consciente sur un support matériel autre que biologique. Selon les tenants de l’IA forte, si à l’heure actuelle il n’y a pas d’ordinateurs ou de robots aussi intelligents que l’être humain, ce n’est pas un problème d’outil mais de conception. Il n’y aurait aucune limite fonctionnelle (un ordinateur est une machine de Turing universelle avec pour seules limites les limites de la calculabilité), il n’y aurait que des limites liées à l’aptitude humaine à concevoir le programme approprié. Elle permet notamment de modéliser des idées abstraites.

Estimation de faisabilité

On peut être tenté de comparer la capacité de traitement de l’information d’un cerveau humain à celle d’un ordinateur pour estimer la faisabilité d’une IA forte. Il s’agit cependant d’un exercice purement spéculatif, et la pertinence de cette comparaison n’est pas établie. Cette estimation très grossière est surtout destinée à préciser les ordres de grandeur en présence.

Un ordinateur typique de 1970 effectuait 107 opérations logiques par seconde, et occupait donc – géométriquement – une sorte de milieu entre une balance de Roberval (1 opération logique par seconde) et le cerveau humain (grossièrement 2 x 1014 opérations logiques par seconde, car formé de 2 x 1012 neurones ne pouvant chacun commuter plus de 100 fois par seconde).

En 2005, un microprocesseur typique traite 64 bits en parallèle (128 dans le cas de machines à double cœur) à une vitesse typique de 2 GHz, ce qui place en puissance brute dans les 1011 opérations logiques par seconde. En ce qui concerne ces machines destinées au particulier, l’écart s’est donc nettement réduit. En ce qui concerne les machines comme Blue Gene, il a même changé de sens.

Le matériel serait donc maintenant présent. Du logiciel à la mesure de ce matériel resterait à développer. En effet, l’important n’est pas de raisonner plus vite, en traitant plus de données, ou en mémorisant plus de choses que le cerveau humain, l’important est de traiter les informations de manière appropriée.

L’IA souligne la difficulté à expliciter toutes les connaissances utiles à la résolution d’un problème complexe. Certaines connaissances dites implicites sont acquises par l’expérience et mal formalisables. Par exemple, qu’est-ce qui distingue un visage familier de deux cents autres ? Nous ne savons clairement l’exprimer.

L’apprentissage de ces connaissances implicites par l’expérience semble une voie prometteuse (voir Réseau de neurones). Néanmoins, un autre type de complexité apparaît, la complexité structurelle. Comment mettre en relation des modules spécialisés pour traiter un certain type d’informations, par exemple un système de reconnaissance des formes visuelles, un système de reconnaissance de la parole, un système lié à la motivation, à la coordination motrice, au langage, etc. En revanche, une fois un tel système conçu et un apprentissage par l’expérience réalisé, l’intelligence du robot pourrait probablement être dupliquée en un grand nombre d’exemplaires.

Diversité des opinions

Les principales opinions soutenues pour répondre à la question d’une intelligence artificielle consciente sont les suivantes :

- Impossible : la conscience serait le propre des organismes vivants, et elle serait liée à la nature des systèmes biologiques. Cette position est défendue principalement par des philosophes et des religieux.

- Problème : Elle rappelle toutefois toutes les controverses passées entre vitalistes et matérialistes, l’histoire ayant à plusieurs reprises infirmé les positions des premiers.

- Impossible avec des machines manipulant des symboles comme les ordinateurs actuels, mais possible avec des systèmes dont l’organisation matérielle serait fondée sur des processus quantiques. Cette position est défendue notamment par Roger Penrose. Des algorithmes quantiques sont théoriquement capables de mener à bien des calculs hors de l’atteinte pratique des calculateurs conventionnels ( complexité en

au lieu de

au lieu de  , par exemple, sous réserve d’existence du calculateur approprié). Au-delà de la rapidité, le fait que l’on puisse envisager des systèmes quantiques en mesure de calculer des fonctions non- turing-calculables (voir Hypercalcul) ouvre des possibilités qui – selon cet auteur – sont fondamentalement interdites aux machines de Turing.

, par exemple, sous réserve d’existence du calculateur approprié). Au-delà de la rapidité, le fait que l’on puisse envisager des systèmes quantiques en mesure de calculer des fonctions non- turing-calculables (voir Hypercalcul) ouvre des possibilités qui – selon cet auteur – sont fondamentalement interdites aux machines de Turing.

- Problème : On ne dispose pas encore pour le moment d’algorithmes d’IA à mettre en œuvre dessus. Tout cela reste donc spéculatif.

- Impossible avec des machines manipulant des symboles comme les ordinateurs actuels, mais possible avec des systèmes dont l’organisation matérielle mimerait le fonctionnement du cerveau humain, par exemple avec des circuits électroniques spécialisés reproduisant le fonctionnement des neurones.

- Problème : Le système en question répondant exactement de la même façon que sa simulation sur ordinateur – toujours possible – au nom de quel principe leur assigner une différence ?

- Impossible avec les algorithmes classiques manipulant des symboles (logique formelle), car de nombreuses connaissances sont difficiles à expliciter mais possible avec un apprentissage par l’expérience de ces connaissances à l’aide d’outils tels que des réseaux de neurones formels, dont l’organisation logique et non matérielle s’inspire des neurones biologiques, et utilisés avec du matériel informatique conventionnel.

- Problème : si du matériel informatique conventionnel est utilisé pour réaliser un réseau de neurones, alors il est possible de réaliser l’IA avec les ordinateurs classiques manipulant des symboles (puisque ce sont les mêmes machines, voir Thèse de Church-Turing). Cette position parait donc incohérente. Toutefois, ses défenseurs (thèse de l’IA forte) arguent que l’impossibilité en question est liée à notre inaptitude à tout programmer de manière explicite, elle n’a rien à voir avec une impossibilité théorique. Par ailleurs, ce que fait un ordinateur, un système à base d’échanges de bouts de papier dans une salle immense peut le simuler quelques milliards de fois plus lentement. Or il peut rester difficile à admettre que cet échange de bouts de papiers « ait une conscience ». Voir Chambre chinoise. Selon les tenants de l’IA forte, cela ne pose toutefois pas de problème.

- Impossible car la pensée n’est pas un phénomène calculable par des processus discrets et finis. Pour passer d’un état de pensée au suivant, il y a une infinité non dénombrable, une continuité d’états transitoires. Cette idée est réfutée par Alain Cardon (Modéliser et concevoir une Machine pensante).

- Possible avec des ordinateurs manipulant des symboles. La notion de symbole est toutefois à prendre au sens large. Cette option inclut les travaux sur le raisonnement ou l’apprentissage symbolique basé sur la logique des prédicats, mais aussi les techniques connexionnistes telles que les réseaux de neurones, qui, à la base, sont définies par des symboles. Cette dernière opinion constitue la position la plus engagée en faveur de l’intelligence artificielle forte.

Des auteurs comme Hofstadter (mais déjà avant lui Arthur C. Clarke ou Alan Turing) (voir le test de Turing) expriment par ailleurs un doute sur la possibilité de faire la différence entre une intelligence artificielle qui éprouverait réellement une conscience, et une autre qui simulerait exactement ce comportement. Après tout, nous ne pouvons même pas être certains que d’autres consciences que la nôtre (chez des humains s’entend) éprouvent réellement quoi que ce soit. On retrouve là le problème connu du solipsisme en philosophie.

Travaux complémentaires

- Le mathématicien de la physique Roger Penrose pense que la conscience viendrait de l’exploitation de phénomènes quantiques dans le cerveau (voir microtubules), empêchant la simulation réaliste de plus de quelques dizaines de neurones sur un ordinateur normal, d’où les résultats encore très partiels de l’IA. Il restait jusqu’à présent isolé sur cette question. Un autre chercheur a présenté depuis une thèse de même esprit quoique moins radicale Andrei Kirilyuk

- Cette spéculation reste néanmoins marginale par rapport aux travaux des neurosciences. L’action de phénomènes quantiques est évidente dans le cas de la rétine (quelques quanta de lumière seulement suffisent à une perception) ou de l’odorat, mais elle ne constitue pas une condition préalable à un traitement efficace de l’information. En effet, le traitement de l’information effectué par le cerveau est relativement robuste et ne dépend pas de l’état quantique de chaque molécule, ni même de la présence ou de la connexion de neurones isolés.

Cela dit, l’intelligence artificielle est loin de se limiter aux seuls réseaux de neurones, qui ne sont généralement utilisés que comme classifieurs. Les techniques de résolution générale de problèmes et la logique des prédicats, entre autres, ont fourni des résultats spectaculaires et sont exploités par les ingénieurs dans de nombreux domaines.

Intelligence artificielle faible

La notion d’intelligence artificielle faible constitue une approche pragmatique d’ ingénieur : chercher à construire des systèmes de plus en plus autonomes (pour réduire le coût de leur supervision), des algorithmes capables de résoudre des problèmes d’une certaine classe, etc. Mais, cette fois, la machine simule l’intelligence, elle semble agir comme si elle était intelligente. On en voit des exemples concrets avec les programmes conversationnels qui tentent de passer le test de Turing, comme ELIZA. Ces programmes parviennent à imiter de façon grossière le comportement d’humains face à d’autres humains lors d’un dialogue. Ces programmes « semblent » intelligents, mais ne le sont pas. Les tenants de l’IA forte admettent qu’il y a bien dans ce cas une simulation de comportements intelligents, mais qu’il est aisé de le découvrir et qu’on ne peut donc généraliser. En effet, si on ne peut différencier expérimentalement deux comportements intelligents, celui d’une machine et celui d’un humain, comment peut-on prétendre que les deux choses ont des propriétés différentes ? Le terme même de « simulation de l’intelligence » est contesté et devrait, toujours selon eux, être remplacé par « reproduction de l’intelligence ».

Les tenants de l’IA faible arguent que la plupart des techniques actuelles d’intelligence artificielle sont inspirées de leur paradigme. Ce serait par exemple la démarche utilisée par IBM dans son projet nommé Autonomic computing. La controverse persiste néanmoins avec les tenants de l’IA forte qui contestent cette interprétation.

Simple évolution, donc, et non révolution : l’intelligence artificielle s’inscrit à ce compte dans la droite succession de ce qu’ont été la recherche opérationnelle dans les années 1960, la Supervision (en anglais : process control) dans les années 1970, l’ aide à la décision dans les années 1980 et le data mining dans les années 1990. Et, qui plus est, avec une certaine continuité.

Il s’agit surtout d’intelligence humaine reconstituée, et de programmation d’un apprentissage.

Estimation de faisabilité

Critères possibles d’un système de dialogue évolué

Le sémanticien François Rastier, après avoir rappelé les positions de Turing et de Grice à ce sujet, propose six « préceptes » conditionnant un système de dialogue évolué, en précisant qu’elles sont déjà mises en œuvre par des systèmes existants :

- objectivité (utilisation d’une base de connaissances par le système)

- textualité (prise en compte d’interventions de plus d’une phrase, qu’elles émanent du système ou de l’utilisateur)

- apprentissage (intégration au moins temporaire d’informations issues des propos de l’utilisateur)

- questionnement (demande de précisions de la part du système)

- rectification (suggestion de rectifications à la question posée, lorsque nécessaire)

- explicitation (explicitation par le système d’une réponse qu’il a apportée précédemment).

Il suggère aussi que le système devrait être en mesure de se faire par lui-même une représentation de l’utilisateur auquel il a affaire, pour s’adapter à lui. De son côté, l’utilisateur a tendance à s’adapter au système à partir du moment où il a bien compris qu’il s’adresse à une machine : il ne conversera pas de la même manière avec un système automatisé qu’avec un interlocuteur humain, ce qui présente pour le concepteur l’avantage pragmatique de simplifier certains aspects du dialogue.

Courants de pensée

La cybernétique naissante des années 1940 revendiquait très clairement son caractère pluridisciplinaire et se nourrissait des contributions les plus diverses : neurophysiologie, psychologie, logique, sciences sociales… Et c’est tout naturellement qu’elle envisagea deux approches des systèmes, deux approches reprises par les sciences cognitives et de ce fait l’intelligence artificielle :

- une approche par la décomposition (du haut vers le bas),

- une approche contraire par construction progressive du bas vers le haut.

Ces deux approches se révèlent plutôt complémentaires que contradictoires : on est à l’aise pour décomposer rapidement ce que l’on connaît bien, et une approche pragmatique à partir des seuls élements que l’on connaît afin de se familiariser avec les concepts émergents est plus utile pour le domaines inconnus. Elles sont respectivement à la base des hypothèses de travail que constituent le cognitivisme et le connexionnisme, qui tentent aujourd’hui (2005) d’opérer progressivement leur fusion.

Cognitivisme

Le cognitivisme considère que le vivant, tel un ordinateur (bien que par des procédés évidemment très différents), manipule essentiellement des symboles élémentaires. Dans son livre La société de l’esprit, Marvin Minsky, s’appuyant sur des observations du psychologue Jean Piaget envisage le processus cognitif comme une compétition d’agents fournissant des réponses partielles et dont les avis sont arbitrés par d’autres agents. Il cite les exemples suivants de Piaget :

- L’enfant croit d’abord que plus le niveau d’eau est élevé dans un verre, plus il y a d’eau dans ce verre. Après avoir joué avec des transvasements successifs, il intègre le fait que la notion de hauteur du liquide dans le verre entre en compétition avec celle du diamètre du verre, et arbitre de son mieux entre les deux.

- Il vit ensuite une expérience analogue en manipulant de la pâte à modeler : la réduction de plusieurs objets temporairement représentés à une même boule de pâte l’incite à dégager un concept de conservation de la quantité de matière.

Au bout du compte, ces jeux d’enfants se révèlent essentiels à la formation de l’esprit, qui dégagent quelques règles pour arbitrer les différents éléments d’appréciation qu’il rencontre, par essais et erreurs.

Connexionnisme

Le connexionnisme, se référant aux processus auto-organisationnels, envisage la cognition comme le résultat d’une interaction globale des parties élémentaires d’un système. On ne peut nier que le chien dispose d’une sorte de connaissance des équations différentielles du mouvement, puisqu’il arrive à attraper un bâton au vol. Et pas davantage qu’un chat ait aussi une sorte de connaissance de la loi de chute des corps, puisqu’il se comporte comme s’il savait à partir de quelle hauteur il ne doit plus essayer de sauter directement pour se diriger vers le sol. Cette faculté qui évoque un peu l’ intuition des philosophes se caractériserait par la prise en compte et la consolidation d’éléments perceptifs dont aucun pris isolément n’atteint le seuil de la conscience, ou en tout cas n’y déclenche d’interprétation particulière.

Synthèse

Trois concepts reviennent de façon récurrente dans la plupart des travaux :

- la redondance (le système est peu sensible à des pannes ponctuelles)

- la réentrance (les composants s’informent en permanence entre eux; cette notion diffère de la réentrance en programmation)

- la sélection (au fil du temps, les comportements efficaces sont dégagés et renforcés)

Les différentes facettes de l’intelligence artificielle

On peut considérer différents dispositifs intervenant, ensemble ou séparément, dans un système d’intelligence artificielle tels que :

- Le dialogue automatique : se faire comprendre en lui parlant,

- Traduction automatique, si possible en temps réel ou très légèrement différé, comme dans le film « Dune »,

- Le traitement automatique des langues,

- Le raisonnement automatique (voir systèmes experts),

- L’ apprentissage automatique,

- La composition musicale automatique (voir les travaux de René-Louis Baron et de l’ Ircam),

- La reconnaissance de formes, des visages et la vision en général, etc.

- Intégration automatique d’informations provenant de sources hétérogènes, ( fusion de données)

- L’ émotion artificielle (voir les travaux de Rosalind Picard sur l’émotion) et l’éventualité d’une subjectivité artificielle

- Etc.

Les réalisations actuelles de l’intelligence artificielle peuvent intervenir dans les fonctions suivantes :

- Aide aux diagnostics

- L’ aide à la décision.

- Résolution de problèmes complexes, tels que les problèmes d’allocation de ressources.

- Assistance par des machines dans les tâches dangereuses, ou demandant une grande précision,

- Automatisation de tâches

- etc.

La conception de systèmes d’IA

Au fil du temps, certains langages de programmation se sont avérés plus commodes que d’autres pour écrire des applications d’intelligence artificielle. Parmi ceux-ci, Lisp et Prolog furent sans doute les plus médiatisés. Lisp constituait une solution ingénieuse pour faire de l’intelligence artificielle en FORTRAN. ELIZA (le premier chatterbot, donc pas de la « véritable » intelligence artificielle) tenait en trois pages de SNOBOL.

On utilise aussi, plus pour des raisons de disponibilité et de performance que de commodité, des langages classiques tels que C ou C++. Lisp a eu pour sa part une série de successeurs plus ou moins inspirés de lui, dont le langage Scheme.

Des programmes de démonstration de théorèmes géométriques simples ont existé dès les années 1960 ; et des logiciels aussi triviaux que Maple et Mathematica effectuent aujourd’hui des travaux d’intégration symbolique qui il y a trente ans encore étaient du ressort d’un étudiant de mathématiques supérieures. Mais ces programmes ne savent pas plus qu’ils effectuent des démonstrations géométriques ou algébriques que Deep Blue ne savait qu’il jouait aux échecs (ou un programme de facturation qu’il calcule une facture). Ces cas représentent donc plus des opérations intellectuelles assistées par ordinateur faisant appel à la puissance de calcul que de l’intelligence artificielle à proprement parler.

Domaines d’application

L’intelligence artificielle a été et est utilisée (ou intervient) dans une variété de domaines tels que :

- la banque, avec des systèmes experts d’évaluation de risque lié à l’octroi d’un crédit (credit-scoring)

- le militaire, avec les systèmes autonomes tels que les drones, les systèmes de commandement et l’aide à la décision

- les jeux

- la médecine, avec les systèmes experts d’aide au diagnostic

- la logistique, au travers d’approches heuristiques de type résolution de problème de satisfaction de contraintes

- l’ éducation

Jeux vidéo

L’intelligence artificielle a par exemple été utilisée depuis longtemps dans la conception de joueurs artificiels pour le jeu d’échecs.

Toutefois, c’est dans les jeux vidéo que l’intelligence artificielle s’est le plus popularisée, et c’est aussi un des domaines où elle se développe rapidement. Celle-ci bénéficie en effet des progrès de l’informatique, avec par exemple les cartes graphiques dédiées qui déchargent le processeur principal des tâches graphiques. Le processeur principal peut désormais être utilisé pour développer des systèmes d’IA plus perfectionnés.

Par exemple l’intelligence artificielle peut être utilisée pour ‘piloter’ des bots (c’est-à-dire les personnages artificiels) évoluant dans les MMOGs ou les mondes virtuels, mais on peut aussi citer son utilisation dans des jeux de simulation, ou pour animer des personnages artificiels.

Dans le domaine du jeu vidéo, l’IA caractérise toute prise de décision d’un personnage (ou d’un groupe) géré par le jeu, et contraint par l’intérêt ludique : une « meilleure » IA ne donne pas forcément un jeu plus jouable, l’objectif est de donner l’illusion d’un comportement intelligent. L’éventail de sujets ( recherche de chemin, animation procédurale, planifications stratégiques…) sont réalisables par différentes techniques classiques issues de deux paradigmes distincts : IA symbolique (automates, script, systèmes multi-agents…), et IA située (réseau de neurones, algorithmes évolutionnistes…) ; où l’une est fortement dépendante de l’expertise humaine, et l’autre de l’expérience en situation. La première approche est globalement préférée, car mieux contrôlée, mais la deuxième est préférée pour certains comportements (déplacement d’une formation, désirs/satisfactions). Elles partagent toutes les mêmes contraintes de ressources restreintes, que ce soit en mémoire, en temps de développement, ou en temps de calcul, même si globalement ces ressources augmentent plus les projets sont récents.

Jusqu’à la fin des années 1990, l’IA dans les jeux vidéo (plus particulièrement dans les jeux en temps réel) a été délaissée par rapport au rendu visuel et sonore. L’« évolution vers des univers toujours plus réalistes, leur peuplement par des personnages […] aux comportements crédibles devient une problématique importante ». Pour éviter ce contraste, et couplé dans le même temps au délestage d’une grosse partie de l’aspect graphique des processeurs vers les cartes graphiques, on constate à cette période une augmentation des ressources investies dans l’IA (temps de développement, ressource processeur). Certains jeux sont précurseurs ( Creatures, Black & White) car l’IA y constitue l’élément central ludique. Partant d’une approche à base de règles rigides, les jeux utilisent alors des IA plus flexibles, diversifiant les techniques mises en œuvre. Aujourd’hui la plupart des jeux vidéo utilisent des solutions ad hoc, il existe néanmoins des solutions middleware et également des solutions matérielles toutefois très minoritaires.

Avec les jeux en réseau, le besoin d’IA a tout d’abord été négligé, mais, particulièrement avec l’apparition des jeux massivement multijoueur, et la présence d’un nombre très important de joueurs humain se confrontant à des personnages non joueur, ces derniers ont un besoin très important de pouvoir s’adapter à des situations qui ne peuvent être prévues. Actuellement ces types de jeux intéressent particulièrement des chercheurs en IA, y trouvant un environnement adéquat pour y éprouver différentes architectures adaptatives.

L’« IA scriptée » est une forme d’intelligence artificielle sans apprentissage, du type : « si le joueur a telle position, alors faire prendre tel chemin à deux PNJ », sans que le logiciel sache que cela encercle le joueur, ou ne varie sa stratégie.

Précurseurs

Si les progrès de l’intelligence artificielle sont récents, ce thème de réflexion est tout à fait ancien, et il apparaît régulièrement au cours de l’histoire. Les premiers signes d’intérêt pour une intelligence artificielle et les principaux précurseurs de cette discipline sont les suivants.

Automates

- Une des plus anciennes traces du thème de « l’homme dans la machine » date de 800 avant notre ère, en Égypte. La statue du dieu Amon levait le bras pour désigner le nouveau pharaon parmi les prétendants qui défilaient devant lui, puis elle « prononçait » un discours de consécration. Les Égyptiens étaient probablement conscients de la présence d’un prêtre actionnant un mécanisme et déclarant les paroles sacrées derrière la statue, mais cela ne semblait pas être pour eux contradictoire avec l’incarnation de la divinité.

- Vers la même époque, Homère, dans L’Iliade (XVIII, 370–421), décrit les automates réalisés par le dieu forgeron Héphaïstos : des trépieds munis de roues en or, capables de porter des objets jusqu’à l’ Olympe et de revenir seuls dans la demeure du dieu ; ou encore, deux servantes forgées en or qui l’assistent dans sa tâche. De même, le Géant de bronze Talos, gardien des rivages de la Crète, était parfois considéré comme une œuvre du dieu.

- Vitruve, architecte romain, décrit l’existence entre le IIIe et le Ier siècle avant notre ère, d’une école d’ingénieurs fondée par Ctesibius à Alexandrie, et concevant des mécanismes destinés à l’amusement tels des corbeaux qui chantaient.

- Héron L’Ancien décrit dans son traité « Automates », un carrousel animé grâce à la vapeur et considéré comme anticipant les machines à vapeur.

- Les automates disparaissent ensuite jusqu’à la fin du Moyen Âge.

- On a prêté à Roger Bacon la conception d’automates doués de la parole; en fait, probablement de mécanismes simulant la prononciation de certains mots simples.

- Léonard de Vinci a construit un automate en forme de lion en l’honneur de Louis XII.

- Gio Battista Aleotti et Salomon de Caus ont construit des oiseaux artificiels et chantants, des flûtistes mécaniques, des nymphes, des dragons et des satyres animés pour égayer des fêtes aristocratiques, des jardins et des grottes.

- René Descartes aurait conçu en 1649 un automate qu’il appelait « ma fille Francine ». Il conduit par ailleurs une réflexion d’un modernisme étonnant sur les différences entre la nature des automates, et celles d’une part des animaux (pas de différence) et d’autre part celle des hommes (pas d’assimilation). Ces analyses en font le précurseur méconnu d’un des principaux thèmes de la science-fiction : l’indistinction entre le vivant et l’artificiel, entre les hommes et les robots, les androïdes ou les intelligences artificielles.

Le canard artificiel de Vaucanson (1738)

- Jacques de Vaucanson a construit en 1738 un « canard artificiel de cuivre doré, qui boit, mange, cancane, barbote et digère comme un vrai canard ». Il était possible de programmer les mouvements de cet automate, grâce à des pignons placés sur un cylindre gravé, qui contrôlaient des baguettes traversant les pattes du canard. L’automate a été exposé pendant plusieurs années en France, en Italie et en Angleterre, et la transparence de l’abdomen permettait d’observer le mécanisme interne. Le dispositif permettant de simuler la digestion et d’expulser une sorte de bouillie verte fait l’objet d’une controverse. Certains commentateurs estiment que cette bouillie verte n’était pas fabriquée à partir des aliments ingérés, mais préparée à l’avance. D’autres estiment que cet avis n’est fondé que sur des imitations du canard de Vaucanson. Malheureusement, l’incendie du Musée de Nijni Novgorod en Russie vers 1879 détruisit cet automate.

- Les artisans Pierre et Louis Jaquet-Droz fabriquèrent parmi les meilleurs automates fondés sur un système purement mécanique, avant le développement des dispositifs électromécaniques. Certains de ces automates, par un système de cames multiples, étaient capables d’écrire un petit billet (toujours le même).

- Le conte d’ Hoffmann (et ballet) L’Homme au sable décrit une poupée mécanique dont s’éprend le héros.

Pensée automatique

Les processus cognitifs peuvent-ils se réduire à un simple calcul ? Et si tel est le cas, quels sont les symboles et les règles à employer ?

Les premiers essais de formalisation de la pensée sont les suivants :

- Raymond Lulle, missionnaire, philosophe, et théologien espagnol du XIIIe siècle, a fait la première tentative pour engendrer des idées par un système mécanique. Il combinait aléatoirement des concepts grâce à une sorte de règle à calcul, un zairja, sur laquelle pivotaient des disques concentriques gravés de lettres et de symboles philosophiques. Il baptisa sa méthode Grand Art (Ars Magna), fondée sur l’identification de concepts de base, puis leur combinaison mécanique soit entre eux, soit avec des idées connexes. Raymond Lulle appliqua sa méthode à la métaphysique, puis à la morale, à la médecine et à l’ astrologie. Mais il n’utilisait que la logique déductive, ce qui ne permettait pas à son système d’acquérir un apprentissage, ni davantage de remettre en cause ses principes de départ : seule la logique inductive le permet.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, au XVIIe siècle, a imaginé un calcul pensant (calculus rationator), en assignant un nombre à chaque concept. La manipulation de ces nombres aurait permis de résoudre les questions les plus difficiles, et même d’aboutir à un langage universel. Leibniz a toutefois démontré que l’une des principales difficultés de cette méthode, également rencontrée dans les travaux modernes sur l’intelligence artificielle, est l’interconnexion de tous les concepts, ce qui ne permet pas d’isoler une idée de toutes les autres pour simplifier les problèmes liés à la pensée.

- George Boole a inventé la formulation mathématique des processus fondamentaux du raisonnement, connue sous le nom d’ algèbre de Boole. Il était conscient des liens de ses travaux avec les mécanismes de l’intelligence, comme le montre le titre de son principal ouvrage paru en 1854 : « Les lois de la pensée » (The laws of thought), sur l’algèbre booléenne.

- Gottlob Frege perfectionna le système de Boole en inventant le concept de prédicat, qui est une entité logique soit vraie, soit fausse (toute maison a un propriétaire), mais contenant des variables non logiques, n’ayant en soit aucun degré de vérité (maison, propriétaire). Cette invention eut une grande importance puisqu’elle permit de démontrer des théorèmes généraux, simplement en appliquant des règles typographiques à des ensembles de symboles. La réflexion en langage courant ne portait plus que sur le choix des règles à appliquer. Par ailleurs, seul l’utilisateur connaît le sens des symboles qu’il a inventés, ce qui ramène au problème de la signification en intelligence artificielle, et de la subjectivité des utilisateurs.

- Bertrand Russell et Alfred North Whitehead publièrent au début du XXe siècle un ouvrage intitulé « Principia mathematica », dans lequel ils résolvent des contradictions internes à la théorie de Gottlob Frege. Ces travaux laissaient espérer d’aboutir à une formalisation complète des mathématiques.

- Kurt Gödel démontre au contraire que les mathématiques resteront une construction ouverte, en publiant en 1931 un article intitulé « Des propositions formellement indécidables contenues dans les Principia mathematica et autres systèmes similaires ». Sa démonstration est qu’à partir d’une certaine complexité d’un système, on peut y créer plus de propositions logiques qu’on ne peut en démontrer vraies ou fausses. L’arithmétique, par exemple, ne peut trancher par ses axiomes si on doit accepter des nombres dont le carré soit -1. Ce choix reste arbitraire et n’est en rien lié aux axiomes de base. Le travail de Gödel suggère qu’on pourra créer ainsi un nombre arbitraire de nouveaux axiomes, compatibles avec les précédents, au fur et à mesure qu’on en aura besoin. Si l’arithmétique est démontrée incomplète, le calcul des prédicats (logique formelle) est au contraire démontré par Gödel comme complet.

- Alan Turing parvient aux mêmes conclusions que Kurt Gödel, en inventant des machines abstraites et universelles (rebaptisées les machines de Turing), dont les ordinateurs modernes sont considérés comme des concrétisations. Il démontre l’existence de calculs qu’ aucune machine ne peut faire (un humain pas davantage, dans les cas qu’il cite), sans pour autant que cela constitue pour Turing un motif pour douter de la faisabilité de machines pensantes répondant aux critères du test de Turing.

- Irving John Good, Myron Tribus et E.T. Jaynes ont décrit de façon très claire les principes assez simples d’un robot à logique inductive utilisant les principes de l’ inférence bayésienne pour enrichir sa base de connaissances sur la base du Théorème de Cox-Jaynes. Ils n’ont malheureusement pas traité la question de la façon dont on pourrait stocker ces connaissances sans que le mode de stockage entraîne un biais cognitif. Le projet est voisin de celui de Raymond Lulle, mais fondé cette fois-ci sur une logique inductive, et donc propre à résoudre quelques problèmes ouverts.

- Robot à logique inductive

- Des chercheurs comme Alonzo Church ont posé des limites pratiques aux ambitions de la raison, en orientant la recherche ( Herbert Simon, Michael Rabin, Stephen Cook) vers l’obtention des solutions en temps fini, ou avec des ressources limitées, ainsi que vers la catégorisation des problèmes selon des classes de difficulté (en rapport avec les travaux de Cantor sur l’infini).

Les questions soulevées par l’Intelligence artificielle

L’intelligence artificielle a connu un essor important pendant les années 1960 et 70, mais à la suite de résultats décevants par rapport aux capitaux investis dans le domaine, son succès s’estompa dès le milieu des années 1980.

Par ailleurs, un certain nombre de questions se posent telles que la possibilité un jour pour les robots d’accéder à la conscience, ou d’éprouver des émotions.

D’après certains auteurs, les perspectives de l’intelligence artificielle pourraient avoir des inconvénients, si par exemple les machines devenaient plus intelligentes que les humains, et finissaient par les dominer, voire (pour les plus pessimistes) les exterminer, de la même façon que nous cherchons à exterminer certaines séquences d’ARN (les virus) alors que nous sommes construits à partir d’ADN, un proche dérivé de l’ARN. On reconnaît le thème du film Terminator, mais des directeurs de société techniquement très compétents, comme Bill Joy de la société Sun, affirment considérer le risque comme réel à long terme.

Toutes ces possibilités futures ont fait l’objet de quantités de romans de science-fiction, tels ceux d’ Isaac Asimov ou William Gibson en passant par Arthur C. Clarke.

Espoirs et méfiances

Une description spectaculaire d’un possible avenir de l’intelligence artificielle a été faite par le professeur I. J. Good :

- « Supposons qu’existe une machine surpassant en intelligence tout ce dont est capable un homme, aussi brillant soit-il. La conception de telles machines faisant partie des activités intellectuelles, cette machine pourrait à son tour créer des machines meilleures qu’elle-même ; cela aurait sans nul doute pour effet une réaction en chaîne de développement de l’intelligence, pendant que l’intelligence humaine resterait presque sur place. Il en résulte que la machine ultra intelligente sera la dernière invention que l’homme aura besoin de faire, à condition que ladite machine soit assez docile pour constamment lui obéir. »

La situation en question, correspondant à un changement qualitatif du principe même de progrès, a été nommée par quelques auteurs « La Singularité ».

Good estimait à un peu plus d’une chance sur deux la mise au point d’une telle machine avant la fin du XXe siècle. La prédiction, en 2011, ne s’est pas réalisée, mais avait imprégné le public : le cours de l’action d’ IBM quadrupla (bien que les dividendes trimestriels versés restèrent à peu de chose près les mêmes) dans les mois qui suivirent la victoire de Deep Blue sur Garry Kasparov. Une large partie du grand public était en effet persuadée qu’IBM venait de mettre au point le vecteur d’une telle explosion de l’intelligence et que cette compagnie en tirerait profit. L’espoir fut déçu : une fois sa victoire acquise, Deep Blue, simple calculateur évaluant 200 millions de positions à la seconde, sans conscience du jeu lui-même, fut reconverti en machine classique utilisée pour l’ exploration de données. Nous sommes probablement encore très loin d’une machine possédant ce que nous nommons de l’intelligence générale, et tout autant d’une machine possédant la base de connaissances de n’importe quel chercheur, si humble soit-il.

En revanche, un programme « comprenant » un langage naturel et connecté à l’Internet serait théoriquement susceptible de construire, petit à petit, une sorte de base de connaissances. Nous ignorons cependant tout aujourd’hui (2011) tant de la structure optimale à choisir pour une telle base que du temps nécessaire à en rassembler et à en agencer le contenu.

L’IA dans la culture populaire

Le thème d’une machine capable d’éprouver une conscience et des sentiments — ou en tout cas de faire comme si — constitue un grand classique de la science-fiction, notamment dans la série de romans d’ Isaac Asimov sur les robots. Ce sujet a toutefois été exploité très tôt, comme dans le récit des aventures de Pinocchio, publié en 1881, où une marionnette capable d’éprouver de l’amour pour son créateur, cherche à devenir un vrai petit garçon. Cette trame a fortement inspiré le film A.I. Intelligence artificielle, réalisé par Steven Spielberg, sur la base des idées de Stanley Kubrick, lui-même inspiré de Brian Aldiss. L’œuvre de Dan Simmons, notamment le cycle d’Hypérion, contient également des exposés et des développements sur le sujet. Autre œuvre majeure de la science fiction sur ce thème, Destination vide, de Frank Herbert, met en scène de manière fascinante l’émergence d’une intelligence artificielle forte.

Dans la fiction

- 1968: 2001 : l’odyssée de l’espace de Stanley Kubrick, inspiré de la nouvelle Sentinelle d’ Arthur C. Clarke, également auteur du scénario du film, avec la lutte entre HAL et Dave ;

- 1969: Colossus : the Forbin project 1969, d’après le roman de Dennis Feltham Jones de 1967 (un système d’IA militaire américain contacte son homologue russe pour qu’ils coopèrent à leur mission commune, éviter la guerre nucléaire… en neutralisant les humains !) a probablement fourni l’idée de départ de Terminator.

- 1981: Blade Runner de Ridley Scott (1981), inspiré du roman éponyme de Philip K. Dick, où des hommes artificiels reviennent sur terre après une mission spatiale (mais n’acceptent pas la mort programmée suite au succès de leur mission) ;

- 1982: Tron de Steven Lisberger (1982), où le Maître contrôle principal (MCP) est un programme d’échec qui a évolué en IA et tente de prendre le contrôle total du système.

- 1983: WarGames de John Badham (1983) avec Matthew Broderick, où David est un pirate informatique qui par défi parvient à contourner les systèmes de sécurité les plus sophistiqués et à maîtriser la dernière génération des jeux informatiques. Mais quand l’inconscient pénètre sans être repéré au cœur de l’ordinateur militaire du Pentagone, ministère de la défense américaine ( Department of Defense ou DoD), il initie par jeu une confrontation d’ampleur mondiale (le système était prévu à la base par son créateur pour réaliser des simulations de guerre mais il ne comprend pas qu’il est maintenant réellement connecté)

- 1985: D.A.R.Y.L., Daryl est un enfant amnésique recueilli sur une route. Mais finalement, le gouvernement cherche à détruire le data analyzing robot youth lifeform ;

- 2001: A.I. Intelligence artificielle de Steven Spielberg, inspiré de la nouvelle de Brian Aldiss Les Supertoys durent tout l’été. Le personnage central est certainement un aboutissement ultime – mais pour l’instant seulement imaginaire – de l’intelligence artificielle : un enfant-robot doué d’émotions et de sentiments ;

- 2004: I, Robot avec Will Smith, inspiré de l’œuvre de Isaac Asimov et thème semblable au film AI ;

- 2005: Furtif de Rob Cohen en 2005. Film mettant en scène un drone (avion sans pilote) de la Navy, doté d’une intelligence artificielle. Son originalité résidant en sa capacité d’apprendre en observant les comportements humains, de les reproduire, lui permettant ainsi de communiquer. Mais dans le film, cela va le mener à sa perte puisque EDDY, le drone va se laisser submerger par ses nouvelles capacités.

- voir aussi

- Liste des robots au cinéma

- Data androïde de Star Trek (Next generation), est un être cybernetique doué d’intelligence, avec des capacités importantes d’apprentissage. Il est officier supérieur sur le vaisseau Enterprise et évolue aux côtés de ses coéquipiers humains qui l’inspirent dans sa quête d’humanité. Il est la représentation type de l’androïde tel qu’il était pensé dans les années 1980.

- La trilogie des Terminator avec Arnold Schwarzenegger, où Skynet cherche à éliminer l’espèce humaine

- Ghost in the Shell, où une IA s’éveille à la conscience ;

Les actualités

L’intelligence artificielle est un sujet d’actualité au 21e siècle :

- En 2004, l’Institut Singularity a lancé une campagne Internet appelée « 3 Lois dangereuses » : « 3 Laws Unsafe » (les 3 lois d’Asimov) pour sensibiliser aux questions de la problématique de l’intelligence artificielle et l’insuffisance des lois d’Asimov en particulier. (Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence 2004).

- En 2005, le projet Blue Brain est lancé, il vise à simuler le cerveau des mammifères, il s’agit d’une des méthodes envisagées pour réaliser une IA. Ils annoncent de plus comme objectif de fabriquer, dans dix ans, le premier « vrai » cerveau électronique.

- En mars 2007, le gouvernement sud-coréen a annoncé que plus tard dans l’année, il émettrait une Charte sur l’éthique des robots, afin de fixer des normes pour les utilisateurs et les fabricants. Selon Park Hye-Young, du ministère de l’Information et de la communication, la Charte reflète les trois lois d’Asimov : La tentative de définition des règles de base pour le développement futur de la robotique.

- En juillet 2009, Californie, conférence organisé par l’Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), ou un groupe d’informaticien se demande s’il devrait y avoir des limites sur la recherche qui pourrait conduire à la perte de l’emprise humaine sur les systèmes informatiques, et où il était également question de l’explosion de l’intelligence (artificielle) et du danger de la singularité technologique conduisant à un changement d’ère, ou de paradigme totalement en dehors du contrôle humain.

- En 2009, le Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) a lancé un projet visant à repenser la recherche en intelligence artificielle, Il réunira des scientifiques qui ont eu du succès dans des domaines distincts de l’IA. Neil Gershenfeld déclare « Nous voulons essentiellement revenir 30 ans en arrière, et de revoir quelques directions aujourd’hui gelées ».

- Novembre 2009. L’ US Air Force cherche à acquérir 2 200 playstation 3 pour utiliser le processeur cell à 7 ou 8 cœurs qu’elle contient dans le but d’augmenter les capacités de leur superordinateur constitué de 336 PlayStation 3 (total théorique 52,8 PetaFlops en double précision). Le nombre sera réduit à 1 700 unités le 22 décembre 2009. Le projet vise le traitement vidéo haute-définition, et l’« informatique neuromorphiques », ou la création de calculateurs avec des propriétés/fonctions similaires au cerveau humain.

- 27 janvier 2010. L’ US Air Force demande l’aide de l’industrie pour développer une intelligence avancée de collecte d’information et avec la capacité de décision rapide pour aider les forces américaines pour attaquer ses ennemis rapidement à leurs points les plus vulnérables et dommageable. L’ US Air Force utilisera une intelligence artificielle, le raisonnement ontologique, et les procédures informatique basées sur la connaissance, ainsi que d’autres traitement de données avancées afin de frapper l’ennemi au meilleur point. D’autre part, d’ici 2020, plus de mille bombardiers et chasseurs F-22 et F-35 de dernière génération, parmi plus de 2 500 avions militaires, commenceront à être équipés de sorte que, d’ici 2040, tous les avions de guerre américains soient pilotés par intelligence artificielle, en plus des 10 000 véhicules terrestres et des 7 000 dispositifs aériens commandés d’ores et déjà à distance.

[/lang_fr]

[lang_en]

Matches between computers and world champions

Artificial Intelligence

TOPIO, a humanoid robot, played table tennis at Tokyo International Robot Exhibition (IREX) 2009.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the intelligence of machines and the branch of computer science that aims to create it. AI textbooks define the field as « the study and design of intelligent agents » where an intelligent agent is a system that perceives its environment and takes actions that maximize its chances of success. John McCarthy, who coined the term in 1956, defines it as « the science and engineering of making intelligent machines. »

The field was founded on the claim that a central property of humans, intelligence—the sapience of Homo sapiens—can be so precisely described that it can be simulated by a machine. This raises philosophical issues about the nature of the mind and the ethics of creating artificial beings, issues which have been addressed by myth, fiction and philosophy since antiquity. Artificial intelligence has been the subject of optimism, but has also suffered setbacks and, today, has become an essential part of the technology industry, providing the heavy lifting for many of the most difficult problems in computer science.

AI research is highly technical and specialized, and deeply divided into subfields that often fail to communicate with each other. Subfields have grown up around particular institutions, the work of individual researchers, the solution of specific problems, longstanding differences of opinion about how AI should be done and the application of widely differing tools. The central problems of AI include such traits as reasoning, knowledge, planning, learning, communication, perception and the ability to move and manipulate objects. General intelligence (or « strong AI ») is still among the field’s long term goals.

History

Thinking machines and artificial beings appear in Greek myths, such as Talos of Crete, the bronze robot of Hephaestus, and Pygmalion’s Galatea. Human likenesses believed to have intelligence were built in every major civilization: animated cult images were worshipped in Egypt and Greece and humanoid automatons were built by Yan Shi, Hero of Alexandria and Al-Jazari. It was also widely believed that artificial beings had been created by Jabir ibn Hayyan, Judah Loew and Paracelsus. By the 19th and 20th centuries, artificial beings had become a common feature in fiction, as in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or Karel Capek’s R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). Pamela McCorduck argues that all of these are examples of an ancient urge, as she describes it, « to forge the gods ». Stories of these creatures and their fates discuss many of the same hopes, fears and ethical concerns that are presented by artificial intelligence.

Mechanical or « formal » reasoning has been developed by philosophers and mathematicians since antiquity. The study of logic led directly to the invention of the programmable digital electronic computer, based on the work of mathematician Alan Turing and others. Turing’s theory of computation suggested that a machine, by shuffling symbols as simple as « 0 » and « 1 », could simulate any conceivable act of mathematical deduction. This, along with concurrent discoveries in neurology, information theory and cybernetics, inspired a small group of researchers to begin to seriously consider the possibility of building an electronic brain.

The field of AI research was founded at a conference on the campus of Dartmouth College in the summer of 1956. The attendees, including John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, became the leaders of AI research for many decades. They and their students wrote programs that were, to most people, simply astonishing: computers were solving word problems in algebra, proving logical theorems and speaking English. By the middle of the 1960s, research in the U.S. was heavily funded by the Department of Defense and laboratories had been established around the world. AI’s founders were profoundly optimistic about the future of the new field: Herbert Simon predicted that « machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do » and Marvin Minsky agreed, writing that « within a generation … the problem of creating ‘artificial intelligence’ will substantially be solved ».

They had failed to recognize the difficulty of some of the problems they faced. In 1974, in response to the criticism of England’s Sir James Lighthill and ongoing pressure from Congress to fund more productive projects, the U.S. and British governments cut off all undirected, exploratory research in AI. The next few years, when funding for projects was hard to find, would later be called an « AI winter ».

In the early 1980s, AI research was revived by the commercial success of expert systems, a form of AI program that simulated the knowledge and analytical skills of one or more human experts. By 1985 the market for AI had reached over a billion dollars. At the same time, Japan’s fifth generation computer project inspired the U.S and British governments to restore funding for academic research in the field. However, beginning with the collapse of the Lisp Machine market in 1987, AI once again fell into disrepute, and a second, longer lasting AI winter began.

In the 1990s and early 21st century, AI achieved its greatest successes, albeit somewhat behind the scenes. Artificial intelligence is used for logistics, data mining, medical diagnosis and many other areas throughout the technology industry. The success was due to several factors: the increasing computational power of computers (see Moore’s law), a greater emphasis on solving specific subproblems, the creation of new ties between AI and other fields working on similar problems, and a new commitment by researchers to solid mathematical methods and rigorous scientific standards.

The artificial intelligence quiz show contestant « Watson », appearing on the US quiz show Jeopardy! in 2011.

[/lang_en]

[lang_en]

On 11 May 1997, Deep Blue became the first computer chess-playing system to beat a reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov. In 2005, a Stanford robot won the DARPA Grand Challenge by driving autonomously for 131 miles along an unrehearsed desert trail. In February 2011, in a Jeopardy! quiz show exhibition match, IBM’s question answering system, Watson, defeated the two greatest Jeopardy! champions, Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings, by a significant margin.

The leading-edge definition of artificial intelligence research is changing over time. One pragmatic definition is: « AI research is that which computing scientists do not know how to do cost-effectively today. » For example, in 1956 optical character recognition (OCR) was considered AI, but today, sophisticated OCR software with a context-sensitive spell checker and grammar checker software comes for free with most image scanners. No one would any longer consider already-solved computing science problems like OCR « artificial intelligence » today.

Low-cost entertaining chess-playing software is commonly available for tablet computers. DARPA no longer provides significant funding for chess-playing computing system development. The XBox 360 gaming system November 2010 Kinect 3D-body-motion interface uses algorithms that emerged from lengthy AI research, but few consumers realize the technology source.

AI applications are no longer the exclusive domain of Department of defense R&D, but are now common place consumer items and inexpensive intelligent toys.

In common usage, the term « AI » no longer seems to apply to off-the-shelf solved computing-science problems, which may have originally emerged out of years of AI research.

Problems

[Top page]

The general problem of simulating (or creating) intelligence has been broken down into a number of specific sub-problems. These consist of particular traits or capabilities that researchers would like an intelligent system to display. The traits described below have received the most attention.

Deduction, reasoning, problem solving

Early AI researchers developed algorithms that imitated the step-by-step reasoning that humans were often assumed to use when they solve puzzles, play board games or make logical deductions. By the late 1980s and ’90s, AI research had also developed highly successful methods for dealing with uncertain or incomplete information, employing concepts from probability and economics.

For difficult problems, most of these algorithms can require enormous computational resources — most experience a » combinatorial explosion »: the amount of memory or computer time required becomes astronomical when the problem goes beyond a certain size. The search for more efficient problem solving algorithms is a high priority for AI research.

Human beings solve most of their problems using fast, intuitive judgments rather than the conscious, step-by-step deduction that early AI research was able to model. AI has made some progress at imitating this kind of « sub-symbolic » problem solving: embodied agent approaches emphasize the importance of sensorimotor skills to higher reasoning; neural net research attempts to simulate the structures inside human and animal brains that give rise to this skill.

Knowledge representation

[Top page]

Knowledge representation and knowledge engineering are central to AI research. Many of the problems machines are expected to solve will require extensive knowledge about the world. Among the things that AI needs to represent are: objects, properties, categories and relations between objects; situations, events, states and time; causes and effects; knowledge about knowledge (what we know about what other people know); and many other, less well researched domains. A complete representation of « what exists » is an ontology (borrowing a word from traditional philosophy), of which the most general are called upper ontologies.

Among the most difficult problems in knowledge representation are:

- Default reasoning and the qualification problem

- Many of the things people know take the form of « working assumptions. » For example, if a bird comes up in conversation, people typically picture an animal that is fist sized, sings, and flies. None of these things are true about all birds. John McCarthy identified this problem in 1969 as the qualification problem: for any commonsense rule that AI researchers care to represent, there tend to be a huge number of exceptions. Almost nothing is simply true or false in the way that abstract logic requires. AI research has explored a number of solutions to this problem.

- The breadth of commonsense knowledge

- The number of atomic facts that the average person knows is astronomical. Research projects that attempt to build a complete knowledge base of commonsense knowledge (e.g., Cyc) require enormous amounts of laborious ontological engineering — they must be built, by hand, one complicated concept at a time. A major goal is to have the computer understand enough concepts to be able to learn by reading from sources like the internet, and thus be able to add to its own ontology.

- The subsymbolic form of some commonsense knowledge

- Much of what people know is not represented as « facts » or « statements » that they could express verbally. For example, a chess master will avoid a particular chess position because it « feels too exposed » or an art critic can take one look at a statue and instantly realize that it is a fake. These are intuitions or tendencies that are represented in the brain non-consciously and sub-symbolically. Knowledge like this informs, supports and provides a context for symbolic, conscious knowledge. As with the related problem of sub-symbolic reasoning, it is hoped that situated AI or computational intelligence will provide ways to represent this kind of knowledge.

Planning

[Top page]

Intelligent agents must be able to set goals and achieve them. They need a way to visualize the future (they must have a representation of the state of the world and be able to make predictions about how their actions will change it) and be able to make choices that maximize the utility (or « value ») of the available choices.

In classical planning problems, the agent can assume that it is the only thing acting on the world and it can be certain what the consequences of its actions may be. However, if this is not true, it must periodically check if the world matches its predictions and it must change its plan as this becomes necessary, requiring the agent to reason under uncertainty.

Multi-agent planning uses the cooperation and competition of many agents to achieve a given goal. Emergent behavior such as this is used by evolutionary algorithms and swarm intelligence.

Learning

Machine learning has been central to AI research from the beginning. In 1956, at the original Dartmouth AI summer conference, Ray Solomonoff wrote a report on unsupervised probabilistic machine learning: « An Inductive Inference Machine ». Unsupervised learning is the ability to find patterns in a stream of input. Supervised learning includes both classification and numerical regression. Classification is used to determine what category something belongs in, after seeing a number of examples of things from several categories. Regression takes a set of numerical input/output examples and attempts to discover a continuous function that would generate the outputs from the inputs. In reinforcement learning the agent is rewarded for good responses and punished for bad ones. These can be analyzed in terms of decision theory, using concepts like utility. The mathematical analysis of machine learning algorithms and their performance is a branch of theoretical computer science known as computational learning theory.

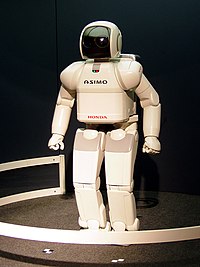

ASIMO uses sensors and intelligent algorithms to avoid obstacles and navigate stairs.

Natural language processing gives machines the ability to read and understand the languages that humans speak. Many researchers hope that a sufficiently powerful natural language processing system would be able to acquire knowledge on its own, by reading the existing text available over the internet. Some straightforward applications of natural language processing include information retrieval (or text mining) and machine translation.

Motion and manipulation

The field of robotics is closely related to AI. Intelligence is required for robots to be able to handle such tasks as object manipulation and navigation, with sub-problems of localization (knowing where you are), mapping (learning what is around you) and motion planning (figuring out how to get there).

Perception

Machine perception is the ability to use input from sensors (such as cameras, microphones, sonar and others more exotic) to deduce aspects of the world. Computer vision is the ability to analyze visual input. A few selected subproblems are speech recognition, facial recognition and object recognition.

Social intelligence

Kismet, a robot with rudimentary social skills

Emotion and social skills play two roles for an intelligent agent. First, it must be able to predict the actions of others, by understanding their motives and emotional states. (This involves elements of game theory, decision theory, as well as the ability to model human emotions and the perceptual skills to detect emotions.) Also, for good human-computer interaction, an intelligent machine also needs to display emotions. At the very least it must appear polite and sensitive to the humans it interacts with. At best, it should have normal emotions itself.

Creativity

A sub-field of AI addresses creativity both theoretically (from a philosophical and psychological perspective) and practically (via specific implementations of systems that generate outputs that can be considered creative, or systems that identify and assess creativity). A related area of computational research is Artificial Intuition and Artificial Imagination.

General intelligence

Most researchers hope that their work will eventually be incorporated into a machine with general intelligence (known as strong AI), combining all the skills above and exceeding human abilities at most or all of them. A few believe that anthropomorphic features like artificial consciousness or an artificial brain may be required for such a project.

Many of the problems above are considered AI-complete: to solve one problem, you must solve them all. For example, even a straightforward, specific task like machine translation requires that the machine follow the author’s argument ( reason), know what is being talked about ( knowledge), and faithfully reproduce the author’s intention ( social intelligence). Machine translation, therefore, is believed to be AI-complete: it may require strong AI to be done as well as humans can do it.

Approaches

[Top page]

There is no established unifying theory or paradigm that guides AI research. Researchers disagree about many issues. A few of the most long standing questions that have remained unanswered are these: should artificial intelligence simulate natural intelligence, by studying psychology or neurology? Or is human biology as irrelevant to AI research as bird biology is to aeronautical engineering? Can intelligent behavior be described using simple, elegant principles (such as logic or optimization)? Or does it necessarily require solving a large number of completely unrelated problems? Can intelligence be reproduced using high-level symbols, similar to words and ideas? Or does it require « sub-symbolic » processing? John Haugeland, who coined the term GOFAI, also proposed that AI should more properly be referred to as synthetic intelligence, a term which has since been adopted by some non-GOFAI researchers. edit] Cybernetics and brain simulation

In the 1940s and 1950s, a number of researchers explored the connection between neurology, information theory, and cybernetics. Some of them built machines that used electronic networks to exhibit rudimentary intelligence, such as W. Grey Walter’s turtles and the Johns Hopkins Beast. Many of these researchers gathered for meetings of the Teleological Society at Princeton University and the Ratio Club in England. By 1960, this approach was largely abandoned, although elements of it would be revived in the 1980s.

Symbolic

[Top page]

When access to digital computers became possible in the middle 1950s, AI research began to explore the possibility that human intelligence could be reduced to symbol manipulation. The research was centered in three institutions: CMU, Stanford and MIT, and each one developed its own style of research. John Haugeland named these approaches to AI « good old fashioned AI » or » GOFAI ».

- Cognitive simulation

- Economist Herbert Simon and Allen Newell studied human problem solving skills and attempted to formalize them, and their work laid the foundations of the field of artificial intelligence, as well as cognitive science, operations research and management science. Their research team used the results of psychological experiments to develop programs that simulated the techniques that people used to solve problems. This tradition, centered at Carnegie Mellon University would eventually culminate in the development of the Soar architecture in the middle 80s.

- Logic-based

- Unlike Newell and Simon, John McCarthy felt that machines did not need to simulate human thought, but should instead try to find the essence of abstract reasoning and problem solving, regardless of whether people used the same algorithms. His laboratory at Stanford ( SAIL) focused on using formal logic to solve a wide variety of problems, including knowledge representation, planning and learning. Logic was also focus of the work at the University of Edinburgh and elsewhere in Europe which led to the development of the programming language Prolog and the science of logic programming.

- « Anti-logic » or « scruffy »

- Researchers at MIT (such as Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert) found that solving difficult problems in vision and natural language processing required ad-hoc solutions – they argued that there was no simple and general principle (like logic) that would capture all the aspects of intelligent behavior. Roger Schank described their « anti-logic » approaches as » scruffy » (as opposed to the » neat » paradigms at CMU and Stanford). [81] Commonsense knowledge bases (such as Doug Lenat’s Cyc) are an example of « scruffy » AI, since they must be built by hand, one complicated concept at a time.

- Knowledge-based

- When computers with large memories became available around 1970, researchers from all three traditions began to build knowledge into AI applications. This « knowledge revolution » led to the development and deployment of expert systems (introduced by Edward Feigenbaum), the first truly successful form of AI software. The knowledge revolution was also driven by the realization that enormous amounts of knowledge would be required by many simple AI applications.

Sub-symbolic

[Top page]

During the 1960s, symbolic approaches had achieved great success at simulating high-level thinking in small demonstration programs. Approaches based on cybernetics or neural networks were abandoned or pushed into the background. By the 1980s, however, progress in symbolic AI seemed to stall and many believed that symbolic systems would never be able to imitate all the processes of human cognition, especially perception, robotics, learning and pattern recognition. A number of researchers began to look into « sub-symbolic » approaches to specific AI problems.

- Bottom-up, embodied, situated, behavior-based or nouvelle AI

- Researchers from the related field of robotics, such as Rodney Brooks, rejected symbolic AI and focused on the basic engineering problems that would allow robots to move and survive. Their work revived the non-symbolic viewpoint of the early cybernetics researchers of the 50s and reintroduced the use of control theory in AI. This coincided with the development of the embodied mind thesis in the related field of cognitive science: the idea that aspects of the body (such as movement, perception and visualization) are required for higher intelligence.

- Computational Intelligence

- Interest in neural networks and » connectionism » was revived by David Rumelhart and others in the middle 1980s. These and other sub-symbolic approaches, such as fuzzy systems and evolutionary computation, are now studied collectively by the emerging discipline of computational intelligence.

Statistical

[Top page]

In the 1990s, AI researchers developed sophisticated mathematical tools to solve specific subproblems. These tools are truly scientific, in the sense that their results are both measurable and verifiable, and they have been responsible for many of AI’s recent successes. The shared mathematical language has also permitted a high level of collaboration with more established fields (like mathematics, economics or operations research). Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig describe this movement as nothing less than a « revolution » and « the victory of the neats. »

Integrating the approaches

- Intelligent agent paradigm

- An intelligent agent is a system that perceives its environment and takes actions which maximizes its chances of success. The simplest intelligent agents are programs that solve specific problems. More complicated agents include human beings and organizations of human beings (such as firms). The paradigm gives researchers license to study isolated problems and find solutions that are both verifiable and useful, without agreeing on one single approach. An agent that solves a specific problem can use any approach that works — some agents are symbolic and logical, some are sub-symbolic neural networks and others may use new approaches. The paradigm also gives researchers a common language to communicate with other fields—such as decision theory and economics—that also use concepts of abstract agents. The intelligent agent paradigm became widely accepted during the 1990s.

- Agent architectures and cognitive architectures

- Researchers have designed systems to build intelligent systems out of interacting intelligent agents in a multi-agent system. [96] A system with both symbolic and sub-symbolic components is a hybrid intelligent system, and the study of such systems is artificial intelligence systems integration. A hierarchical control system provides a bridge between sub-symbolic AI at its lowest, reactive levels and traditional symbolic AI at its highest levels, where relaxed time constraints permit planning and world modelling. [97] Rodney Brooks’ subsumption architecture was an early proposal for such a hierarchical system.

Tools

[Top page]

In the course of 50 years of research, AI has developed a large number of tools to solve the most difficult problems in computer science. A few of the most general of these methods are discussed below.

Search and optimization

Many problems in AI can be solved in theory by intelligently searching through many possible solutions: Reasoning can be reduced to performing a search. For example, logical proof can be viewed as searching for a path that leads from premises to conclusions, where each step is the application of an inference rule. Planning algorithms search through trees of goals and subgoals, attempting to find a path to a target goal, a process called means-ends analysis. Robotics algorithms for moving limbs and grasping objects use local searches in configuration space. Many learning algorithms use search algorithms based on optimization.

Simple exhaustive searches are rarely sufficient for most real world problems: the search space (the number of places to search) quickly grows to astronomical numbers. The result is a search that is too slow or never completes. The solution, for many problems, is to use » heuristics » or « rules of thumb » that eliminate choices that are unlikely to lead to the goal (called » pruning the search tree »). Heuristics supply the program with a « best guess » for what path the solution lies on.

A very different kind of search came to prominence in the 1990s, based on the mathematical theory of optimization. For many problems, it is possible to begin the search with some form of a guess and then refine the guess incrementally until no more refinements can be made. These algorithms can be visualized as blind hill climbing: we begin the search at a random point on the landscape, and then, by jumps or steps, we keep moving our guess uphill, until we reach the top. Other optimization algorithms are simulated annealing, beam search and random optimization.

Evolutionary computation uses a form of optimization search. For example, they may begin with a population of organisms (the guesses) and then allow them to mutate and recombine, selecting only the fittest to survive each generation (refining the guesses). Forms of evolutionary computation include swarm intelligence algorithms (such as ant colony or particle swarm optimization) and evolutionary algorithms (such as genetic algorithms and genetic programming).

Logic

Logic is used for knowledge representation and problem solving, but it can be applied to other problems as well. For example, the satplan algorithm uses logic for planning and inductive logic programming is a method for learning.

Several different forms of logic are used in AI research. Propositional or sentential logic is the logic of statements which can be true or false. First-order logic also allows the use of quantifiers and predicates, and can express facts about objects, their properties, and their relations with each other. Fuzzy logic, [112] is a version of first-order logic which allows the truth of a statement to be represented as a value between 0 and 1, rather than simply True (1) or False (0). Fuzzy systems can be used for uncertain reasoning and have been widely used in modern industrial and consumer product control systems. Subjective logic models uncertainty in a different and more explicit manner than fuzzy-logic: a given binomial opinion satisfies belief + disbelief + uncertainty = 1 within a Beta distribution. By this method, ignorance can be distinguished from probabilistic statements that an agent makes with high confidence.

Default logics, non-monotonic logics and circumscription are forms of logic designed to help with default reasoning and the qualification problem. Several extensions of logic have been designed to handle specific domains of knowledge, such as: description logics; situation calculus, event calculus and fluent calculus (for representing events and time); causal calculus; belief calculus; and modal logics.

Probabilistic methods for uncertain reasoning

Many problems in AI (in reasoning, planning, learning, perception and robotics) require the agent to operate with incomplete or uncertain information. AI researchers have devised a number of powerful tools to solve these problems using methods from probability theory and economics.

Bayesian networks are a very general tool that can be used for a large number of problems: reasoning (using the Bayesian inference algorithm), learning (using the expectation-maximization algorithm), planning (using decision networks) and perception (using dynamic Bayesian networks). Probabilistic algorithms can also be used for filtering, prediction, smoothing and finding explanations for streams of data, helping perception systems to analyze processes that occur over time (e.g., hidden Markov models or Kalman filters).

A key concept from the science of economics is « utility »: a measure of how valuable something is to an intelligent agent. Precise mathematical tools have been developed that analyze how an agent can make choices and plan, using decision theory, decision analysis, information value theory. These tools include models such as Markov decision processes, dynamic decision networks, game theory and mechanism design.

Classifiers and statistical learning methods